Interview with translator Debali Mookerjea-Leonard

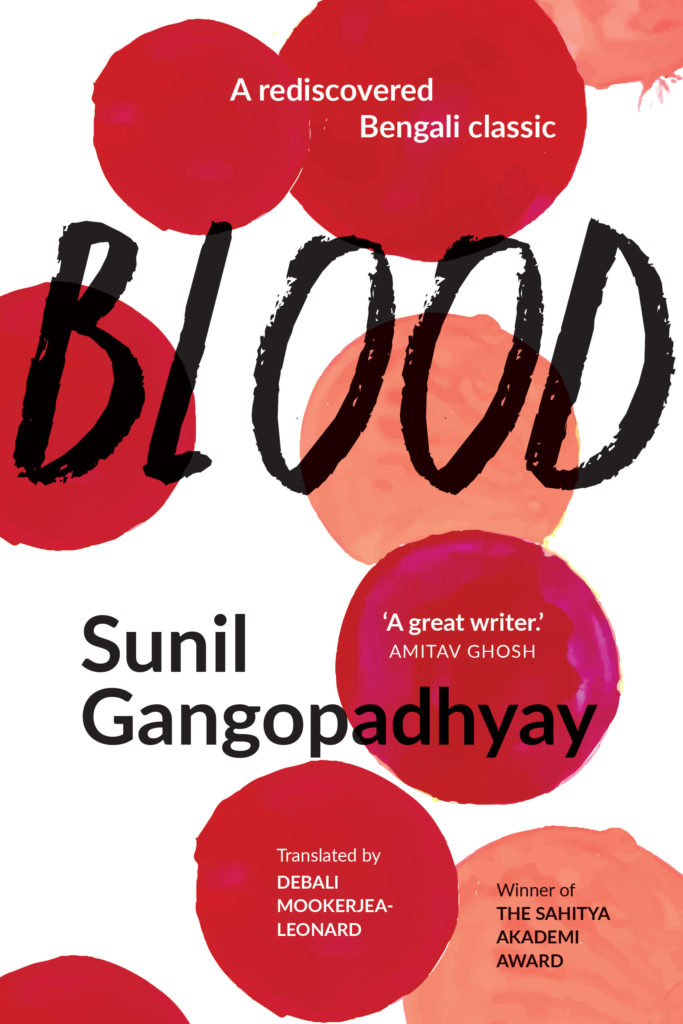

Debali Mookerjea-Leonard is a Bengali translator, author, and professor of English and world literature. She lives in Virginia with her husband and plants. She has translated the late Sunil Gangopadhyay’s novel Blood. Set in Britain and America of the late 60s and early 70s, it is about a highly successful Bengali physicist Tapan who settles abroad. Despite all the successes he has garnered he is unable to put to rest the trauma he suffered as a child when his father was killed by a British officer. This occurred a little before India attained Independence. Coincidentally he meets Alice in London; she is the daughter of his father’s killer. Tapan’s world goes topsy-turvy as he tries to figure out what to do since he nurses a visceral hatred for the former colonial rulers of India. It is a peculiar situation to be in given that he has more or less decided to relocate abroad and never to return to India. It impacts his relationship with Alice too who is more than sympathetic to his feelings and is willing to let the past be bygones but it is a demon that Tapan finds hard to forget. He does go to India briefly to attend a wedding and meet his paternal grandmother — someone whom he loves dearly and who had lost two sons in the Indian Freedom Struggle. So much so that the Indian politicians are now keen to bestow upon her a monthly allowance recognising her sons’ contribution as freedom fighters. It is upon meeting his grandmother, who is past eighty and who witnessed much sorrow in her lifetime, that Tapan realises it is best to forget and forgive that which happened in the past and move on. Otherwise the past becomes an impossible burden to shed. Blood is a brilliantly translated novel that does not seem dated despite its preoccupations with the Indian Freedom struggle and a newly independent India. For all the stories and their intersections, it is evident that Blood is a modern novel which is worth resurrecting in the twenty-first century. The issues it raises regarding immigrants, familial ties, free will, social acceptance, loneliness, etc will resonate with many readers. As Debali says in the interview that “As an Indian expatriate myself, I found Sunil Gangopadhyay’s frank treatment of the subject refreshing.”

Sunil Gangopadhyay, who died in 2012, was one of Bengal’s best-loved and most-acclaimed writers. He is the author of over a hundred books, including fiction, poetry, travelogues and works for children. He won the Sahitya Akademi Award for his novel Those Days. This novel Blood was first published in 1973.

Here is a lightly edited interview conducted via email with the translator:

1 . How long did it take you to translate Blood? In the translator’s note you refer to two editions of the novel. What are the differences in the two editions?

I was on sabbatical during the spring semester of 2018 and Blood was my new project. I began working on it around the middle of January and completed the first draft in May. However, I let it sit for a year before returning to revise it.

I chose to use the second edition (1974) of Blood, rather than the first (1973), because the author made a few revisions. The alterations are minor, mostly cosmetic, and include replacing a few words in the text. These are mostly English words transliterated into Bengali: For instance, in Chapter 1, when Tapan asks Alice if she has the right glasses for serving champagne she responds, in the first edition, with “Don’t be fussy, Tapan” whereas, in the second, she says, “Don’t be funny, Tapan.” The revised second edition also corrects spelling errors and misprints.

2. The book may have been first published in 1973 but it seems a very modern text in terms of its preoccupations especially the immigrants. What were the thoughts zipping through your mind while translating the story?

To me the novel’s handling of immigrant concerns feels brutally honest. Blood refuses to romanticise the expatriate condition as exile and, instead, adopts an ironic stance towards immigrant angst, homesickness, and nostalgia. Yet, the irony is tempered with pathos in the narration’s uncovering of immigrant dilemmas. For instance, an Indian immigrant uneasy about her fluency in English chooses to stay indoors, but remains enamoured with England which she nevertheless cannot fully experience. Through the exchanges between the novel’s protagonist Tapan and his friend Dibakar, Blood also offers the realistic view that immigration is often driven by practical considerations. As an Indian expatriate myself, I found Sunil Gangopadhyay’s frank treatment of the subject refreshing.

This does not mean that western societies get a pass in the novel. Through situations both small and large the novel exposes the racist and anti-immigration views prevailing in the United Kingdom, during the 1960s. That said, Blood is also critical of racial prejudice amongst Indians. Given current debates around immigration and citizenship both in India and across the globe, the novel’s treatment of this subject remains relevant.

Connected to issues of migration and home, the novel brings to the fore complex questions about homeland and belonging, uncovering how the location of “home” has been rendered unstable through the Partition’s severing of birthplace and homeland.

3. What is the methodology you adopt while translating? For instance, some translators make rough translations at first and then edit the text. There are others who work painstakingly on every sentence before proceeding to the next passage/section. How do you work?

For me it is a mix of both. I typically plan on translating a text it in its entirety before proceeding with the revisions but this intention is usually short-lived and seldom lasts beyond the first few pages. I find it difficult to progress until the translation feels most appropriate to the context, fits the voice, and fully conveys the meaning of the original. While translating Blood I have spent entire mornings deciding between synonyms. It is like working on a jigsaw puzzle because there is only one piece/word that fits. And sometimes I have had to redraft an entire sentence (even entire paragraphs) to elegantly capture the sense of the whole!

4. What are the pros and cons a translator can expect when immersed in a project?

First, the cons, the impulse to interpret. And the pros: the joy of being able to partake in the (re-)making of something beautiful.

5. Are there any questions that you wished you could have asked Sunil Gangopadhyay while translating his novel?

Were he alive, I would have requested him to read a completed draft of my translation.

6. What prompted you to become a professional translator?

My translation-work is driven primarily by the love of the text and the desire to find it a larger audience. In the future, I hope to be able to devote more time to it.

There is also a pedagogical dimension to this. In my capacity as a teacher of world literature, I aim to expose students to the vast and rich body of vernacular writings from the Indian subcontinent, inevitably through translations. And from personal experiences in the classroom, I know that many of my students are genuinely curious about writings from around the world. Blood is a small step in that direction. It is a book I want to teach.

7. Which was the first translated book you recall reading? Did you ever realise it was a translation?

I believe the first translated book I read was one of the many “Adventures of Tintin”, The Secret of the Unicorn. But children’s books aside, the book that came to mind immediately upon reading your question is Gregory Rabassa’s translation of Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. It may not have been the first translated work I read, but it ranks among the most memorable ones. This is because while I knew that Marquez wrote in Spanish, Rabassa’s translation preserved the novel’s artistic qualities so meticulously that it lulled me into thinking that I was reading the original. It is a quality I aspire to bring to my work.

8. How you do assess /decide when to take on a translation project?

Not to sound self-absorbed, but my decision is based largely on how deeply the work moves me. My first translation project involved a short story by the Bengali author Jyotirmoyee Devi, entitled “Shei Chheleta” (“That Little Boy”). It depicts the predicament of a young woman who lost a family-member in the Partition riots. The author handled the subject with great sensitivity without resorting to the maudlin. The story would not leave me alone. I had to translate it because I needed to share it, and discuss it with friends and colleagues who did not read Bengali. Similarly, Gangopadhyay’s novel intrigued me when I first read it. I thought about the characters long after I had finished the book, imagined their lives beyond the novel. I knew that one day I would translate it. It hibernated within me for years because, in the meanwhile, there were Ph.D. dissertations to write and research to publish. Finally, a sabbatical gave me the gift of time, and I just had to do it.

9. How would you define a “good” translation?

Preserving the artistic, poetic, and, of course, propositional content of the original is central to my understanding of a good translation. To resort to the old cliché, it is about conveying the letter and, perhaps more importantly, the spirit of the original. The translated text, I feel, must itself be a literary work, a work imbued with the beauty of the original. Additionally, readability is fundamental. Therefore, I asked family members and friends to read the draft translation for lucidity and fluency. For this reason, I am immensely gratified by your observation about Blood that, “It has been a long time since I managed to read a translation effortlessly and not having to wonder about the original language. There is no awkwardness in the English translation”.

10. Can the art of translating be taught? If so, what are the significant landmarks one should be aware of as a translator?

It is difficult for me to say since I never received any formal training in translation-work. To me, translation is more than just an academic exercise, it is an act of love — love for the text itself, love of the language, and the love of reading. For me the best preparation was reading, and reading widely, even indiscriminately. While my love of reading was nurtured from early childhood by my mother, I had the privilege of being exposed to some of the finest works of world literature through my training in comparative literature at Jadavpur University in Calcutta and, later, in literature departments in America.

11. Do you think there is a paradox of faithfulness to the source text versus readability in the new language?

The translator walks a tightrope between the two, where tipping towards either side is perilous. A translation is, by definition, derivative, so fidelity to the original text is essential. Yet, a translation of a literary work is much more than a stringing together of words in another language. It is itself a literary work. And it is incumbent upon the translator not only to make the work accurate and readable but also literary in a way that is faithful to the literary qualities of the original.

12. What are the translated texts you uphold as the gold standard in translations? Who are the translators you admire?

Gregory Rabassa’s translation of Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude; J.M. Cohen’s translation of Cervantes’ Don Quixote; and A.K. Ramanujan’s translation of Ananthamurthy’s Samskara.

More recently, Supriya Chaudhuri, Daisy Rockwell, and Arunava Sinha have produced quality translations from Indian languages.

Blood is published by Juggernaut Books ( 2020).

3 May 2020