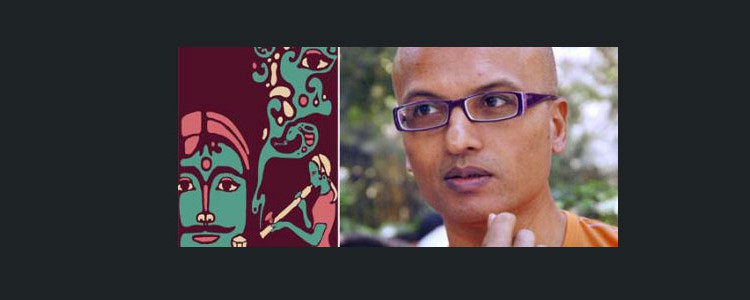

Jeet Thayil, “Narcopolis” — a review and an interview, Feb 2012

(Congratulations to Jeet Thayil for being shortlisted for the ManBooker Prize yesterday. I am reproducing a review and an interview with him that was published earlier in the year.)

Baptised into One Body

‘Narcopolis’ has created a new benchmark in literary fiction. Kudos to Jeet Thayil for having made a neat transition from verse to prose

Narcopolis

Jeet Thayil

Faber and Faber Limited, London

Pages: 304

Price: 499

Year: 2011

Narcopolis is a ground-breaking novel in the use of language, structure of its prose and content. Zeenat is a eunuch who leads the story, by meeting all the other characters in the book. The action is set in Rashid’s opium den on Shuklaji Street, in Old Bombay. All shades of humanity stop by. The air is thick with narcotic fumes. It is peppered with interesting conversation, led mostly by Zeenat. She is a neo-literate, who, by the end of the novel, is a voracious reader who reads anything that comes her way. There is a Bengali, a drug-addict too, of whom Jeet Thayil says in a recent Facebook post that “he appears with his name unchanged. I knew him about 30 years ago in Shuklaji Street, Bombay. I’d heard of Pablo’s (Bartholomew’s) photo, and then I finally saw it and the intervening years disappeared.”

There is Mr Lee, the Chinaman who settled in Bombay. After escaping persecution from Communist China he operated a legendary opium den. Upon his death he bequeathed Zeenat a couple of exquisitely crafted handmade opium pipes that were at least 500 years old. These helped Zeenat forge a new relationship with Rashid and made his business prosper like never before.

According to the omniscient narrator, the novel is by, “a thinking someone who’s writing these words, who’s arranging time in a logical chronological sequence, someone with an overall plan, an engineer-god in the machine, well, that isn’t the I who’s telling this story, that’s the I who’s being told, thinking of my first pipe at Rashid’s, trawling my head for images, a face, a bit of music, or the sound of someone’s voice, trying to remember whether it was like, the past, recall it as I would the landscape and light of a foreign country, because that’s what it is, not fiction or dead history but a place you lived in once and cannot return to…” He goes on to say that “…my memory is like blotting paper, my full-of-holes, porous, shreddable non-memory, remembering details from 30 years ago …” (but) …“I’m not separating but connecting, I’m giving in to the lovely stories.”

Narcopolis is a multi-layered novel, quite unlike any other in contemporary literary fiction. Probably, being a poet first, helps Jeet Thayil in the structure of his prose. There are instances when parts of the story read as if it were poetry. The introduction to the novel is a paragraph of seven pages, but it is not dull to read. In other sections, it is as if one is reading performance poetry. The passage has a strong rhythm, a well-defined story of its own (contributes to the main narrative, but works well as a standalone too) and has a chorus (quite unusual for prose).

It is fascinating to read how the author incorporates various literary discourses in Narcopolis, with delicious references to the dadas of the English literature canon like John Ruskin and TS Eliot. The overwhelming presence of classical literature like the Bible and Illiad seem to have influenced the writing. There are strong echoes of a fundamental teaching of Christ that everyone – all the minorities like the Gentiles, the circumcised, and prostitutes – are equal for God. “For by one Spirit are we all baptized into one body, whether we be Jews or Gentiles, whether we be bond or free; and have been all made to drink into one Spirit.” In the structure of the novel itself, of a story within a story, and the balanced structure with Mr Lee’s autobiographical account forming the centerpiece, it is reminiscent of the Illiad. Is it a mere coincidence that the narrator reveals his name as Ullis? There are moments that create a physical reaction, quite like any other I have experienced while reading fiction, but I would attribute it to the power of the author’s writing.

The importance of the urban landscape and historical events like the 1991 communal riots in Mumbai form a neat backdrop to the novel. Unlike other fiction, where the socio-political climate intrudes forcefully, this one abstains, as if life carries on normally. For an addict, it is the next fix that is of paramount importance, nothing else really. The novel is powerful, but also very disturbing to read. Maybe the reader’s sensibilities are lulled into an artificial sense of well-being with plenty of literary fiction that abounds. So much so that even ‘conflict fiction’ is easier to stomach, but the everyday rawness and jagged edges of this text is what probably adds to the disturbance.

Narcopolis is a book that has created a new benchmark in literary fiction. Kudos to Jeet Thayil for having made a clever and a neat transition from verse to prose.

‘Most Indian publishers rejected the manuscript’

Author Jeet Thayil in conversation with Jaya Bhattacharji Rose, via e-mail

Being a poet and a performance poet, has it influenced your style of writing prose?

A novel is a different sort of animal. It has its own engine. Unlike a poem, which can be written in a burst, a novel requires sustained work. You have to be physically fit and you have to live in your mind for long periods of time.

With all first novels, there is always a strong semi-autobiographical sense. Is it true of Narcopolis as well?

There is an autobiographical element in Narcopolis, but it is hidden in the story and it isn’t important. This is why the narrator is treated like a cipher, he is the least well-developed character in the novel.

Your novel is replete with characters who would normally be dismissed as inconsequential, invisibilised or totally marginalised by society. But here you have given them centre stage. I don’t know why, but the teachings of Christ keep resounding in my mind while reading the novel. Am I way off the mark to be making this connection?

You’re not off the mark. Religion is a constant in the book, specifically, Hinduism, Islam and Christianity. It is a kind of narrative thread.

I find it very peculiar that Dimple/Zeenat who begins the novel as a neo-literate, by the end of the novel is reading reams and reams of anything that she can lay her hands upon. Why so? Or is this a strong autobiographical element making its presence felt?

Dimple’s character, and the growth of her character is, in many ways, the point of the novel. There’s nothing autobiographical about it. She’s a ‘charismatic autodidact’ who chooses reading as a way to escape narrowness. She reads every day and reads everything she can find, and later, as soporo, she puts her reading to good use.

I have always found it a pleasure to read your writing. You are so very correct in the use of language. Now, I see it unfurl in this novel. I cannot think of too many other instances in fiction, where the words leap out at you in rhythm (for instance, p. 23-24). Or, the introduction. It is an interior monologue, the prose is more like poetry. Apart from Henry James, I cannot recall any other prose that has such large chunks of matter clumped together, yet suck you in immediately into the text. Am I right or wrong? Have you consciously or subconsciously tinkered with the prose structure as if it were poetry?

I worked hard on the language, by that I mean, on the sentences. I often read them aloud to get the rhythm right. I don’t think it has anything to do with poetry or prose, it’s just writing to the best of one’s ability.

This kind of multilayered reading is today reserved for poetry. So, I am glad to see it in prose. Recently, your book was termed as a cult in the making. But was that your intention?

It wasn’t my intention to write ‘an instant cult classic’, but I understand what he’s getting at. This is not the kind of novel that will find its readers, or reviewers, in the first few months of its existence. It will find its readership in time, or so I hope.

Could you please explain why do you have such a long break in China? I have read it twice and have not understood its purpose at all! Unless you are merely playing with time and “giving into the lovely stories”. The China section is a crucial part of the story.

In the first four decades of the 19th century, Bombay became India’s premier metropolis, because of the opium trade. The East India Company and a small group of Parsi ship owners transformed the city from a collection of malarial islands to India’s financial capital. How can you write a history of opium in Bombay and skip the connection with China? I was lucky in a way. I grew up in Hong Kong and I was familiar with the Chinese. Also, I’d lived in Bombay for many years. I was uniquely, if accidentally, placed to tell the story.

I have heard that this manuscript received numerous rejection slips, but ultimately your agent, David Godwin, sold it for a neat sum at FBF 2010. Is that correct? Was this edited considerably after you submitted it for publication or was it accepted, without any major change?

Most Indian publishers rejected the manuscript. It was depressing at the time, but it turned out to be a stroke of luck. The manuscript was picked up by an editor, Lee Brackstone, and a publishing house, Faber, who were and are passionate about the book. I’m glad it went to the right house.

From the print issue of Hardnews : FEBRUARY 2012

http://www.hardnewsmedia.com/2012/02/4374

1 Comment