Sunjeev Sahota, “The Year of the Runaways”

‘It really is a pathetic thing. To mourn a past you never had. Don’t you think?’

‘It really is a pathetic thing. To mourn a past you never had. Don’t you think?’

p.216

Sunjeev Sahota’s The Year of the Runaways is his second novel. According to Granta in 2014, he was one of the promising writers from Britain. I have liked his writing ever since I reviewed his debut novel, Ours are the Streets, for DNA in 2011. The first chapter of The Year of the Runaways was extracted in Granta, Best of British novelists. It is about a few men from India who choose to migrate to the UK. They are from different socio-economic classes. Tochi is a chamar, an “untouchable”, from Bihar who had gone to Punjab in search of a job, but with his father falling ill, returned to the village. Unfortunately during the massacres perpetrated by the upper castes his family was destroyed too. So he gathered his life-savings and left India. The other men who leave around the same time are Avtar and Randeep, migrants from Punjab. Randeep is from a “better” social class since his father is a government officer and he is able to migrate using the “visa-wife” route. But when these young men get to Britain, they are “equal”. It is immaterial whether they are working as bonded labour or on construction sites or cooking or even cleaning drains. They are willing to do any task as long as it allows them to stay on in the country. Apparently living a life of uncertainty and in constant fear of raids by the immigration officers is far preferable to life at home.

The women characters of Narinder, Baba Jeet Kaur and Savraj are annoying. Maybe they are meant to be. Given how much effort and time has been spent figuring out the male characters, the women come across as flat characters. Narinder, Randeep’s visa-wife, seems to have the maximum social mobility in society as well as amongst these migrants but she remains a mystery. It is only towards the end of the novel that just as she begins to find her voice and asserts herself, the story comes to an abrupt end.

I like Sunjeev Sahota’s writing for the language and sensual descriptions. He makes visible what usually lurks in the shadows, confined to the margins. He makes it come alive. It is remarkable to see the lengths a storyteller can go to tell a story that has a visceral reaction in the reader. Also it is admirable that while living in Leeds, UK, Sunjeev Sahota has written a powerful example of South Asian fiction that is set in Britain without ever really showing a white except for the old man Randeep had befriended while working at the call centre. Sunjeev Sahota admires Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children. ( It was also the first novel he read as he admits in the YouTube interview on Granta’s channel.) Rushdie too has given a glowing endorsement to The Year of the Runaways saying, “All you can do is surrender, happily, to its power”. ( http://granta.com/Salman-Rushdie-on-Sunjeev-Sahota/) True. The only way to read this novel is to surrender to it. But has Sunjeev Sahota broken new ground as his literary idol, Rushdie did with his award-winning novel? The purpose of literary fiction is to make the reader unsettled rather than just hold a mirror up to the reality. As a tiny insight into the hardships economic migrants experience this novel is astounding. But it falls short of being thought-provoking and disturbing or breaking new ground in literary fiction. I doubt it.

Sunjeev Sahota’s gaze on India is an example of poverty porn in literature. He has got the migration patterns, the hostility at ground level in Bihar and Punjab and the nasty descriptions of the Ranvir Sena or the Maheshwar Sena as they are referred to in the novel accurately. ( I think the novel alludes to these massacres as described in this wonderful article by G. Sampath in the Hindu, published on 22 August 2015 http://www.thehindu.com/sunday-anchor/sunday-anchor-g-sampaths-article-on-children-of-a-different-law/article7569719.ece ) Disappointingly Sunjev Sahota’s voice is clunky at times and comes across as well-researched but a trifle jagged in the Indian parts. The British bits are brilliant as if to the Manor born, which Sunjeev Sahota is! Much is explained by what he hopes to explore in this novel in an interview he gave Granta ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=65mtLCbODCk : 23 April 2013) :

What does it mean being unmoored from your homeland and what does that do to a person and subsequent generations? What happens to that hold that is created? What fills it? Then where does one go from there?

This is a strong and fresh voice. Sunjeev Sahota must be read even if this novel ends with a bit of a convenient ending. This is an author whose trajectory in contemporary literature will be worth mapping.

The Year of the Runaway is wholly deserving to be on the ManBooker longlist 2015 but I will be pleasantly surprised to see it on the shortlist.

Sunjeev Sahota The Year of the Runaways Picador India, Pan Macmillan India, New Delhi, 2015. Hb. pp. 480 Rs 599

27 August 2015

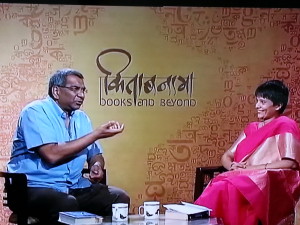

An interview with writer, publisher and anthologist, David Davidar regarding his new book, A Clutch of Indian Masterpieces. It is a collection of 39 short stories by Indian writers. It consists of translations and those written originally in English and has been published by Aleph Book

An interview with writer, publisher and anthologist, David Davidar regarding his new book, A Clutch of Indian Masterpieces. It is a collection of 39 short stories by Indian writers. It consists of translations and those written originally in English and has been published by Aleph Book  Company. This episode of Kitaabnama was recorded on 10 April 2015.

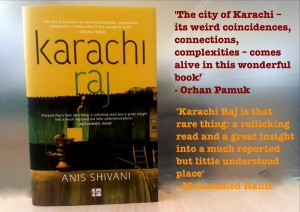

Company. This episode of Kitaabnama was recorded on 10 April 2015. Anis Shivani has been a writer for many years. He is known as a short story writer and a poet. Karachi Raj is his debut novel. It was nearly ten years in the making. It is about a group of people across social classes who meet. Their lives get intertwined in a manner that is not easily expected in a very class conscious society existing in Pakistan today. Anis Shivani is a critic too. An example of his literary criticism is this splendid three-part essay he wrote for Huffington Post on contemporary American Literature. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/anis-shivani/we-are-all-neoliberals-no_b_7546606.html?ir=India&adsSiteOverride=in ;

Anis Shivani has been a writer for many years. He is known as a short story writer and a poet. Karachi Raj is his debut novel. It was nearly ten years in the making. It is about a group of people across social classes who meet. Their lives get intertwined in a manner that is not easily expected in a very class conscious society existing in Pakistan today. Anis Shivani is a critic too. An example of his literary criticism is this splendid three-part essay he wrote for Huffington Post on contemporary American Literature. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/anis-shivani/we-are-all-neoliberals-no_b_7546606.html?ir=India&adsSiteOverride=in ;