Women In Publishing: Championing The Written Word

BusinessWorld magazine as part of Women Day celebrations did a special issue on Women ( 20 March 2017). Sanjitha Rao Chaini asked some of the prominent women in women in Indian publishing to share their views on one book that has inspired them. I spoke about Chitra Banerjee Divakurni.

BusinessWorld magazine as part of Women Day celebrations did a special issue on Women ( 20 March 2017). Sanjitha Rao Chaini asked some of the prominent women in women in Indian publishing to share their views on one book that has inspired them. I spoke about Chitra Banerjee Divakurni.

If there is one sector that celebrates women and is run by women, then it has to be the publishing industry in India. A Ficci report says that the Indian publishing industry is among the top seven nations in the world. Sanjitha Rao Chaini asked some of the prominent women in Indian publishing to share their views on one book that has inspired them

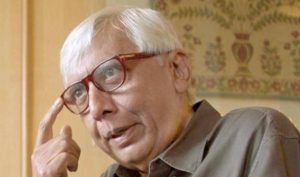

URVASHI BUTALIA is a publisher and writer. She is co-founder of Kali for Women, India’s first feminist publisher, and is now director of Zubaan

If I were to pinpoint one book that has been important to me as a feminist and a feminist publisher, it is a two-volume edited edition of Women Writing in India 600 B.C. to the Present Day, (1991) edited by Susie Tharu and Ke Lalita published by Oxford University Press India. The book is a compilation of the writings of hundreds of women from across many different Indian languages. Apart from being a stunning resource for those of us whose lives are shaped by feminism, it is also a book that gives the lie to the widespread belief that women do not and did not write. It shows that right from the time of Buddhism, women had been producing wonderful literary works, many of which did not see the light of day because of the male domination and hold of knowledge and knowledge production. There are many varieties of writing in the books, many genres, poetry, fiction, essay, memoir, dialogue… and you can go back to it again and again.

PRIYA KAPOOR is Editorial Director, Roli Books, co-owner, CMYK

Anita Desai’s Clear Light of Day is a book that has stayed with me since I read it for the first time over 20 years ago. The book was first published in 1980 and I first read it as a part of literature class in high school and have read it twice since. The book stayed with me because it is subtle, delicate and it lingers much after you have finished reading it — like a great book should. The book is about childhood, family, loss, nostalgia, separation and forgiveness — universal themes that travel very well. You can relate to the characters, their impulses, thought process and weaknesses.

Desai describes the book as her most autobiographical to date and her power of observation is evident in the way she describes people, nature, her setting — Delhi (Old and New). Even though the novel doesn’t have a plot, it holds your attention and made me want to revisit it to find hidden gems.

PRIYA DORASWAMY is Founder, Lotus Lane Literary

PRIYA DORASWAMY is Founder, Lotus Lane Literary

Arshia Sattar’s Lost Loves: Exploring Rama’s Anguish (Penguin, 2011), is one of my all-time favourite books. The book is permanently on my bedside table. Her luminous exploration of Sita and Rama, particularly their motivations, and actions as mortals which are utterly inspiring, devastating, tragic and yet beautiful, is what makes this book so special.

The essays which are very much relevant to the now, but also timeless, brings to the fore notions of free will, complexity in relationships, and the universality of the human condition. To quote Sattar from Lost Loves, “by relocating Rama and Sita in a literary…universe”, she has indeed made “their existential conflicts and resolutions newly accessible and inspiring”.

Sattar is a PhD in South Asian Languages and Civilizations from the University of Chicago.

RADHIKA MENON is Publishing Director, Tulika Books

What comes to my mind is a non-fiction book on gender issues called Gender Talk: Big Hero, Size Zero by Tulika. This book tackles the gender issues head on and demystifies them. The tone is conversational so as not to intimidate the reader. Interestingly, this is a collaboration between three young women — two writers with Gender Studies backgrounds (Anusha Hariharan and Sowmya Rajendran), and an illustrator (Niveditha Subramaniam) — who maintain a balanced and humorous counter-dialogue between the text and the illustrations. With a clear and gentle approach, they uncover truths, untruths, semi-truths and myths using everyday examples as well as references to popular media, and explore what it means socially and culturally to belong to a certain gender. Gender Talk: Big Hero, Size Zero is a much needed non-fiction book not just for teens and young adults, but also for parents and teachers to initiate discussions and dialogue on difficult issues.

PREETI SHENOY is an author and artist. Her last book It’s All In The Planets (Westland) was published in 2016

I First discovered Anita Nair about 10 years ago when I read Ladies Coupe. I loved the writing and how Nair emphasised the way Indian women are treated in society, very realistically, without any sugar-coating. If I had to pick one work of contemporary fiction, by an Indian woman, I would choose Nair’s The Alphabet Soup For Lovers (HarperCollins India, 2015). The prose flows as easily as the recipes, which Komathi —a character in the book, a cook through whose eyes the story unfolds — conjures up. Each chapter is named after a South Indian dish, with Komathi learning the English alphabets by comparing them to the dishes she makes. The loveless marriage that Lena is trapped in, the film star who comes to stay over, the coffee estates where the book is set, all of it comes alive, and it transported me to a world where I was happy to be lost in. When it ended I was left longing for more, just like a well-cooked meal, and therein lies the triumph of the writer.

MANJIRI PRABHU is an author and an independent film-maker for TV. Her last book The Trail Of Four (Bloomsbury) was published in February

My favourite contemporary Indian woman author is Sudha Murty. She has played several roles in her life — she is a prolific bestseller author, a social worker and a philanthropist amongst other things. She wants women to believe in themselves and to unleash the enormous power in them to achieve their goals. I like her writing because I think it comes straight from the heart. Her stories are interesting with a simple but engrossing and emotional narrative and touch a core inside you. Because they are stories about you and me. About characters we can relate to. I feel that her life’s experiences reappear in the form of stories, as well as people who have influenced her in her life, like her grandparents. Writers like Sudha Murty will always remain important to us. Her books propagate much-needed values in an entertaining manner and make it easy for us to understand life, which nowadays seems to be getting more and more complicated.

JAYA BHATTACHARJI ROSE is an international publishing consultant and blogger

For me, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s books have always elegantly examined multi-cultural identities and what it means to be an Indian, an American or a desi (people from the Indian sub-continent or South Asia who live abroad). Her stories engage with the immigrant story specifically from the point of view of the woman. In Before We Visit The Goddess, young Tara epitomises the new generation of American-Indians, not ABCD (American Born Confused Desis) anymore but with a distinct identity of their own. The novel examines these many layers of cultures, interweaving the traditional and contemporary. It is also the first time men and women play an equal role in her story.

To her credit, Divakaruni never presents a utopian scenario focusing only on women and excluding any engagement with men and society. Instead she details the daily negotiations and choices women face that slowly help them develop into strong personalities. The popularity of her books is evident: The Palace of Illusions was among the top 3 bestsellers at the World Book Fair.

Divakaruni’s next book is going to be worth looking out, as it is about Sita.

This article was published in BW Businessworld issue dated ‘March 20, 2017’ with cover story titled ‘Most Influential Women 2017’