(The following article was commissioned in 2015 by Sarah Odedina for the Read Quarterly. With her permission I am posting it here. On 15 August 2017 India celebrates it’s seventieth anniversary of independence from the British. )

15 August 1947 India won its independence from the British. It had been a long freedom struggle. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, “Father of the Nation”, is recognised as one of its leaders especially with his non-violent method of protest. His birthday, 2 October, is a national holiday. When the British decided to leave the subcontinent they did so after partitioning it into two nations—India and Pakistan.

The uprising of 1857[1] was influential in instilling in the Indians “a rudimentary sense of national unity” that when a genuine Indian freedom movement began within a few decades later it inspired the leaders with the hope that their British masters could be defeated. Significant highlights were the Partition of Bengal, new words such as Swaraj ( “self-rule”), Swadeshi (self-reliance) and Boycott ( of all foreign goods and products), Satyagraha, Jallianwala Bagh ( massacre of peaceful protestors by General Dyer in Amritsar), Chauri Chaura ( burning of a police station, killing 22 policemen on duty), rise of communalism with “parties based on religion like the Muslim League, the Hindu Mahasabha and the Rashtriya Swayam Sevak Sangh …these parties only cared for their own communities, it was to their advantage if they could divide the country around religion.”[2]The Dandi March or the salt satyagraha, the Civil Disobedience Movement, Quit India Movement, and Independence.

It is now nearly 70 years since Independence, three generations removed from the momentous events. The freedom struggle still exists in living memory as it is not too far back in time. Yet for children, history is a mish-mash in their minds — the Harappan civilisation, the Mughals, Mauryan Empire and British India/freedom struggle are a blur. This is where literature plays a crucial role in offering perspectives.

****

Globally children’s literature is understood to include fiction and non-fiction, a category distinct from literature used as textbooks and supplementary readers in schools. In India these fine lines are blurred. For the toddlers and primary school students there is variety of material available – fiction, folktales, mythology, non-fiction. As the pressure of school curriculum increases on students the focus shifts from reading for pleasure to textbooks. Till recently this attitude was deeply ingrained in society. Now the slow shift to reading for pleasure is perceptible. It is a coalescing of multiple factors –an increase in income of parents allowing disposable income available for purchase of books, a rise in publishing and retailing for children, establishment of specialist bookshops, increase in direct marketing efforts by publishers like book fairs and book clubs in schools and growth in popularity of children’s literature festivals like Bookaroo[3] has made the category of children and young adult book publishing the fastest growing and lucrative category in India. (It also helps when the target audience/market of less than 25 year olds constitutes 40% of the 1.3 billion Indians.)

Children’s literature with the theme of independence is found in school material and trade lists. In the 40s (actually from 30s onward if not earlier) the best children’s literature came out in Bal Sakha – a Hindi Magazine brought out by Bengalis settled in Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh. Some of the best writers, including Premchand, were first published here. This magazine dealt with the issue of independence, presenting it to children in what still seems a fairly contemporary way[4]. In 1957 two publishing houses were established – National Book Trust ( NBT) [5]and Children’s Book Trust ( CBT)[6]. According to Navin Menon, editor, CBT, every year in August Children’s World “publish[es] content related to Independence either written by children or stories/ articles contributed by adults.” Amar Chitra Katha (ACK)[7], specialise in comics, usually the first introduction to children on folktales, Indian mythology and stories about the freedom struggle published its first title on freedom struggle, Rani of Jhansi[8] on 1 Feb 1974, around the 25th anniversary of Independence. Historical accounts by writer and niece of India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, Nayantara Sahgal’s The Story of India’s Freedom Movement (1970) continues to be in print[9]. As she told me in an email, “The freedom movement is part of our modern history. Obviously it is important for young people to know their country’s history.”

Writing for children about the independence movement began to pick up pace in the early 1980s when CBT published writers like Nilima Sinha’s Adventure before Midnight[10]. In 1984 after the assassination of the prime minister, Delhi saw terrible communal clashes. It led to writers like Urvashi Butalia, Ritu Menon and Amitav Ghosh drawing parallels between their experiences with that of Partition. In the 1990s preparations for the fiftieth anniversary celebrations of Indian independence began. To commemorate it there were a deluge of books. For instance, Shashi Deshpande’s novel The Narayanpur Incident and Macmillan published The First Patriots (series editor, Mini Krishnan) consisting of short illustrated biographies[11]. Biographies, bordering on hagiographies, are the most popular genre for introducing children to this period in history. These books sell extremely well since it supplements school textbooks. Scholastic India with its Great Lives[12], Puffin India with Puffin Lives and Hachette India with What they did, What they Said? series have profiled freedom fighters registering steady sales too. Gandhi is a popular subject of biographies. From picture books ( A Man Called Bapu and We call her Ba on his wife, Kasturba), standard biographical accounts, profusely illustrated with photographs like DK India’s Eyewitness Gandhi and graphic novels like Gandhi: My Life is my message ( Gandhi – Mera Jeevan Hi Mera Sandesh). [13] An unusual book is Everyone’s Gandhi by Subir Shukla[14] which looked at Gandhi from children’s point of view. It asked provocative questions. It was syndicated in some 75 newspapers (English and regional languages) and the author used to get 500 postcards every week from children across the country, proving that it is possible to approach independence in a manner that generates serious response. Paro Anand, writer and founder, Literature in Action[15] says “I loved this book because it brought me closer to Gandhi. It took the capital letter out of it because made me see him like a human being who I could be not a saint or god who I could never aspire to be. I have used the book often with kids urging them to be a Gandhi for 5 minutes every day, in a single act of kindness or a single act of care. To me empathy is a very important component of kid lit.”

is a popular subject of biographies. From picture books ( A Man Called Bapu and We call her Ba on his wife, Kasturba), standard biographical accounts, profusely illustrated with photographs like DK India’s Eyewitness Gandhi and graphic novels like Gandhi: My Life is my message ( Gandhi – Mera Jeevan Hi Mera Sandesh). [13] An unusual book is Everyone’s Gandhi by Subir Shukla[14] which looked at Gandhi from children’s point of view. It asked provocative questions. It was syndicated in some 75 newspapers (English and regional languages) and the author used to get 500 postcards every week from children across the country, proving that it is possible to approach independence in a manner that generates serious response. Paro Anand, writer and founder, Literature in Action[15] says “I loved this book because it brought me closer to Gandhi. It took the capital letter out of it because made me see him like a human being who I could be not a saint or god who I could never aspire to be. I have used the book often with kids urging them to be a Gandhi for 5 minutes every day, in a single act of kindness or a single act of care. To me empathy is a very important component of kid lit.”

Now there are a variety of books available in terms of writing styles and formats. For instance late Justice Leila Seth’s  fabulous book on the Preamble of the Indian Constitution – We, The Children of India[16]; graded readers with pictures like Bharati Jagannathan’s movingly told One Day in August[17], Nina Sabnani’s heart-warming animation film (later book) based on a true story Mukund and Riaz [18]and Samina Mishra’s Hina in the Old City[19] — all focused on Partition and

fabulous book on the Preamble of the Indian Constitution – We, The Children of India[16]; graded readers with pictures like Bharati Jagannathan’s movingly told One Day in August[17], Nina Sabnani’s heart-warming animation film (later book) based on a true story Mukund and Riaz [18]and Samina Mishra’s Hina in the Old City[19] — all focused on Partition and  Ruby Hembrom’s award-winning picture book Disaibon Hul on the Santhal Rebellion of 1855[20]. Young adult fiction inevitably has the story of one person caught up in the dynamics of the movement. So the author tries to take a micro level view and build upon that. For instance, Chitra Bannerjee Divakurni’s Neela: A Victory Song[21], Jamila Gavin’s Surya trilogy — The Wheel of Surya (1992), The Eye of the Horse (1994) and The Track of the Wind (1997)[22], Irfan Master’s A Beautiful Lie[23],[24] Siddharth Sharma’s award-winning debut novel The Grasshopper’s Run[25] which focuses on the

Ruby Hembrom’s award-winning picture book Disaibon Hul on the Santhal Rebellion of 1855[20]. Young adult fiction inevitably has the story of one person caught up in the dynamics of the movement. So the author tries to take a micro level view and build upon that. For instance, Chitra Bannerjee Divakurni’s Neela: A Victory Song[21], Jamila Gavin’s Surya trilogy — The Wheel of Surya (1992), The Eye of the Horse (1994) and The Track of the Wind (1997)[22], Irfan Master’s A Beautiful Lie[23],[24] Siddharth Sharma’s award-winning debut novel The Grasshopper’s Run[25] which focuses on the  Kohima war and Mathangi Subramanian’s Dear Mrs. Naidu[26] about a young girl who corresponds with Sarojini Naidu through her diary. Forthcoming is the retelling in English of Khwaja Ahmad Abbas’s Bharat Mata ke Paanch Roop ( Urdu) by his niece Syeeda Hameed[27]. Award winning historian-turned-writer, Subhadra Sen Gupta has written a clutch of biographies, historical fiction, picture books and nonfiction titles with the freedom struggle as the literary backdrop[28]. Roshen Dalal has published India at 70 ( 2017) chronicling the seven decades since Independence.

Kohima war and Mathangi Subramanian’s Dear Mrs. Naidu[26] about a young girl who corresponds with Sarojini Naidu through her diary. Forthcoming is the retelling in English of Khwaja Ahmad Abbas’s Bharat Mata ke Paanch Roop ( Urdu) by his niece Syeeda Hameed[27]. Award winning historian-turned-writer, Subhadra Sen Gupta has written a clutch of biographies, historical fiction, picture books and nonfiction titles with the freedom struggle as the literary backdrop[28]. Roshen Dalal has published India at 70 ( 2017) chronicling the seven decades since Independence.

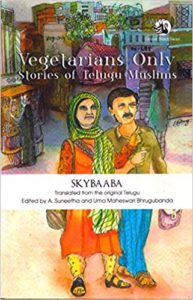

Some other examples of literature are listed by writer Deepa Agarwal, “Subhadra Kumari Chauhan’s popular poem Jhansi ki Rani and Makhanlal Chaturvedi’s Pushp ki Abhilasha. Outstanding historical novels on patriotic themes were written by Manhar Chauhan, like Lucknow ki Loot (The looting of Lucknow) and Bihar ke Bahadur (Brave men of Bihar) both published by National Publishing Company in 1978. His series of sixteen novels about British rule Angrez Aaye aur Gaye (The British came and went) is a monumental work with each book standing alone and yet connected with the others. In Urdu Allama Iqbal’s collection Hindustani Bacchon ke Qaumi Geet and Zakir Hussain’s Abbu Khan ki Bakri are on the theme of freedom. Pandit Brij Narain Chakbast’s patriotic poems, Hamara Watan dil se Pyara, Watan Ko Hum Watan Humo Mubarak, from the collection Subhe Watan were meant for children. In Marathi V.H. Hadap wrote patriotic stories ranging from historical to modern times; his Sattavanachi Satyakatha is about the heroes of the 1857 revolution like Mangal Pande, Tatya Tope and Rani Laxmibai. In fact the centenary … was celebrated in 1957 with many books for children about the people who participated. Vasant Varkhedkar’s Sattavancha Senani is a novel on the life of Tatya Tope.” In Telugu Komuram Bheem: A children’s Novel on a Tribal Hero by Bhupal is about the tribal rebel from Telengana, published by Vennela Prachuranalu (Telugu)[29]. CBT also has a book on Gunda Dhar/ Bhumkal revolt of the Bastar tribal area.

Apart from written literature in India oral histories play a very important role too. Target, a popular children’s magazine, started a comic strip in the mid-eighties called “Freedom’s Children”, where a freedom fighter was profiled based upon extensive interviews. Prominent writers and illustrators collaborated for this project. At the end of each strip a photograph of the actual person was published. Now some schools organise interactions between grandparents with students to recount their memories of independence movement. Many times it is discovered that the children are unaware of the trauma the older generation experienced as if the elders want to protect the younger generation from the horrors they witnessed.

Vatsala Kaul-Banerjee, Publisher, Children & Reference Books, Hachette India says, “General response to these books is quite good. Our children take their cues from USA/ UK, so they do not look at India too much. … I do not think there is enough experimentation in children’s writing to create fiction in this area, so far.” Tina Narang, publisher, Scholastic India adds “Since this is a period in our recent history for which a wealth of detail is available, relevant research material is easy to come by for authors[30] who have written Independence-themed stories. But that I think is the biggest stumbling block. Most such stories tend to become stereotypical in their portrayal of that period and of independence as a valiant struggle by a group of noble and brave souls. There is little or no independent analysis of this struggle or attempt to question the motives, methods or outcomes (partition included).” Sudeshna Shome Ghosh, (then) Editorial Director, Red Turtle echoes this, “We do need to do more books that present a more diverse view of the independence movement and that talks about the role of women or tribals or gives other kinds of alternate views.” Radhika Menon, founder, Tulika Books agrees, “Now we would like to do something that includes the contemporary discourses on the freedom struggle. Something that reflects a more inclusive idea of the freedom struggle with all its complexities so that the reader is urged to think and question rather than be left with certainties about history in her/his mind which tend to be rigid. The challenge is of course to make such a book reader friendly for the pre-teen age group.” Ruby Hembrom, publisher, Adivaani is clear when she says, “If we were to do a book on this period, I wouldn’t feature the Indian Nationalists who have been done to death in textbooks first and have hijacked the ‘independence’ space. I would do Jaipal Singh Munda and his eclipsed role in the constituent Assembly for example.”

Writing about Indian independence and the freedom movement for children is a tricky area since it raises more questions than helps map it. There is an apparent shift in the styles of writing over the generations of writers. From the writer like their subject (usually evident in biographies) have a sense of pride at being an independent and self-reliant nation to contemporary writers whose fiction is based research for using history to comment upon the present politics and social status of marginalised groups. Disaibon Hul is ostensibly about the revolt as mentioned in the book, the introduction refers to “outsiders”, and the story is about the fight against the British. It concludes with “Almost 160 years have passed since the Hul. We are alive but still not the owners of our lives? What will it take for us to be really free?” The term “outsider” is left open-ended. Siddhartha Sharma says he wrote The Grasshopper Run because “I wanted to explain how the Assamese and Nagas got along earlier, unlike today. To contemporary Indians, I wanted to show what the people of the region are like, and how history turned out for us.” [31] Mathangi began writing Dear Mrs Naidu when working in government schools and angadwadis and discovered Sarojini Naidu whose letters she was reading. Mathani realised that Naidu was so human compared to the “demigods of independence” students learned about. She adds, “I think there is a lot of literature on the theme of independence that focuses on a couple of the male freedom fighters, and I’d like to see this change. History is such a powerful force: it shapes the way we think about ourselves, and the way we think about the possibilities for our futures. I want to see more histories of women freedom fighters, and freedom fighters who were not elite. I want to see more literature that helps children understands that heroes are just people with a lot of guts and passion, and that everyone has the capacity for greatness.”[32]

I asked eminent historian Romila Thapar, “What are the events/perspectives and aspects of the freedom struggle that you would recommend are also included in the narratives of the freedom movement?” She replied via email, “You have posed a difficult question. My reaction would be that we need to acquaint children with situations that went into the making of what one may call a ‘wholesome’ society. Not the stories that encourage divisiveness and violence but stories that underline in subtle ways the values of a plural society that we once were. This is disappearing fast and it will be an uphill task to retrieve this as we shall have to do in future years. The goal of the national movement was such that communities came together for a cause and set aside what separated them. It is these moments that need to be remembered in the present times. Often they can be more easily seen in activities related to regional and local history. It may be worth doing a little investigation into how people in rural areas and small towns remember the recent past.”

This observation gains significant urgency when a Muslim man is lynched by a mob on the outskirts of Delhi for his food habits[33]. Noted Hindi journalist Ravish Kumar’s who met a young man, Prashant, at the site says he showed no remorse at the death of Akhlaq, “Instead, he asked us that after the partition, when it had been decided that Hindus will stay here and Muslims will go to Pakistan, why did Gandhi and Nehru ask Muslims stay back in India?… These are the typical beliefs that keep the pot of communalism boiling.” Ravish says he lost the heated argument and could only wonder dismayed, “Who are those people who have left young men like Prashant to be misled by the purveyors of false histories?” Ironically this happened on 2 October, the birthday of Mahatma Gandhi, a man recognised worldwide for his belief in nonviolence.

[1] In A Children’s History of India Subhadra Sen Gupta refers to the events of 1857 and the widespread anger that ensued being an eye-opener for the British “who believed that they were ruling over a peaceful society reconciled to British rule”.

[2] – ibid-

[3] Bookaroo Children’s Literature Festival

[4] Email correspondence with Subir Shukla, Principal Coordinator, IGNUS-erg and formerly associated with NBT. He wrote a few books at this time too.

[5] National Book Trust (NBT), India is a part of the Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India. It was established in 1957 and publishes in English, Hindi and some other Indian languages. It also organizes the annual World Book Fair, New Delhi to which publishers gravitate from around the world

[5] National Book Trust (NBT), India is a part of the Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India. It was established in 1957 and publishes in English, Hindi and some other Indian languages. It also organizes the annual World Book Fair, New Delhi to which publishers gravitate from around the world and country. NBT and CBT between them have published many books, many continue to be in demand such as The Story of Swarajya by Vishnu Prabhakar (Hindi), Jawaharlal Nehru by Tara Ali Baig, Stories From Bapu’s Life by Uma Shankar Joshi (Gujarati), Jallianwala Bagh by Bhisham Sahni (Hindi), Bapu by FC Fretus and How India Won Freedom by Krishna Chaitanya. Email from Rubin DCruz, Editor, NBT. He has also put together an invaluable annotated catalogue of select children’s books in India, Children’s Books 2014, published by National Centre for Children’s Literature, NBT.

and country. NBT and CBT between them have published many books, many continue to be in demand such as The Story of Swarajya by Vishnu Prabhakar (Hindi), Jawaharlal Nehru by Tara Ali Baig, Stories From Bapu’s Life by Uma Shankar Joshi (Gujarati), Jallianwala Bagh by Bhisham Sahni (Hindi), Bapu by FC Fretus and How India Won Freedom by Krishna Chaitanya. Email from Rubin DCruz, Editor, NBT. He has also put together an invaluable annotated catalogue of select children’s books in India, Children’s Books 2014, published by National Centre for Children’s Literature, NBT.

[6] Children’s Book Trust ( CBT) established by cartoonist Shankar in 1957. Its objective is the promotion and production of well-written, well-illustrated and well-designed books for children at prices within the reach of the average Indian child. CBT

[6] Children’s Book Trust ( CBT) established by cartoonist Shankar in 1957. Its objective is the promotion and production of well-written, well-illustrated and well-designed books for children at prices within the reach of the average Indian child. CBT  publications include an illustrated monthly magazine in English, Children’s World. Shankar also set up the Association of Writers and Illustrators for Children (AWIC). Shankar started the Shankar’s International Children’s Competition in 1949, and as a part of it, the Shankar’s On-the-Spot Painting Competition for Children in 1952. He instituted an annual Competition for Writers of Children’s Books in 1978. Some of the CBT titles are Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose by Dr. Lakshmi Sahgal & Col. P.K. Sahgal, Adventure before Midnight by Nilima Sinha, The Return Home by Sarojini Sinha, The Treasure Box by Sarojini Sinha, Kamla’s Story: The Saga Of Our Freedom by Surekha Panandiker, Ira Saxena, & Nilima Sinha, A Pinch Of Salt Rocks an Empire by Sarojini Sinha and Operation Polo by A. K. Srikumar and the 12 volumes on freedom fighters Our Leaders or Mahan Vyaktitwa ( English and Hindi). Some of the original titles in Hindi are Aprajita, Hamare Yuva Balidani and Barah Baras ka Vijeta. Email sent by Navin Menon

publications include an illustrated monthly magazine in English, Children’s World. Shankar also set up the Association of Writers and Illustrators for Children (AWIC). Shankar started the Shankar’s International Children’s Competition in 1949, and as a part of it, the Shankar’s On-the-Spot Painting Competition for Children in 1952. He instituted an annual Competition for Writers of Children’s Books in 1978. Some of the CBT titles are Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose by Dr. Lakshmi Sahgal & Col. P.K. Sahgal, Adventure before Midnight by Nilima Sinha, The Return Home by Sarojini Sinha, The Treasure Box by Sarojini Sinha, Kamla’s Story: The Saga Of Our Freedom by Surekha Panandiker, Ira Saxena, & Nilima Sinha, A Pinch Of Salt Rocks an Empire by Sarojini Sinha and Operation Polo by A. K. Srikumar and the 12 volumes on freedom fighters Our Leaders or Mahan Vyaktitwa ( English and Hindi). Some of the original titles in Hindi are Aprajita, Hamare Yuva Balidani and Barah Baras ka Vijeta. Email sent by Navin Menon

[7] Amar Chitra Katha (ACK) founded by Anant Pai or Uncle Pai specializes in publishing comics. These comics are usually the first introduction to children about stories of the freedom struggle stories. The ACK titles are Rani of Jhansi (date of publication, 1 Feb 1974), Subhash Chandra Bose (1 March 1975), Chandrashekhar Azad (15 August 1977), the Rani of Kittur ( 1 July 1978), Bhagat Singh ( 15 March 1981), Rash Behari Bose ( 15 May 1982), Veer Savarkar ( 15 May 1984), Mangal Pande ( 1 June 1985), Jallianwala Bagh ( 1 June 1986), Beni Madho and Pir Ali (1st Sept.1983), Velu Thampi (1st May 1980), Senapati Bapat ( 1 February 1984), Surjya Sen (October 2010), Vivekananda (15th October 1977), Rabindranath Tagore (20th may 1977), Babasaheb Ambedkar (15th April 1979), Lokmanya Tilak (1st August 1980), Lal Bahadur Shastri (1st October 1982), Mahatma Gandhi – The Early days (1st June 1989), Jayaprakash Narayan (15th January 1980), Jawaharlal Nehru (November 1991), Subramania Bharati (1st December 1982), Deshbandhu Chitaranjan Das (1st November 1985), The Story of the Freedom Struggle (August 1997)

[8] Rani Lakshmibai was one of the leaders of the uprising of 1857. She also became a symbol of the resistance to British Rule.

[9] Nayantara Sahgal The Story of India’s Freedom Red Turtle, an imprint of Rupa Publications, New Delhi, 2013. First published 1970.

[10] Midnight refers to the coming of Freedom and this book describes the events that preceded it. It is about a group of teenagers who participated in the Quit India movement and tried to hoist the tricolour in Patna. It was selected for the International White Raven List for libraries.

[11] Tipu Sultan, The Rani of Jhansi, Kattabomman (the rebel of Pudukottai), Pazhassi Raja (Kerala) and Bhagat Singh. The idea for these series was to write about various legendary heroes and heroines who played a pioneering part in the un-enslaving of the country. According to biographer Shreekumar Varma, “Pazhassi Raja Kerala Varma was one of the earliest such free dom fighters. He fought the marauding armies of both the British and Tipu Sultan. His story is full of adventure and thrill, intrigue and treachery, a case-book of bravery. The book is profusely illustrated. It was heavily researched. The surviving members of the Raja’s family were interviewed at Pazhassi and information was gathered from many books and historical records. The text in the book is but a fraction of the material actually obtained.”

dom fighters. He fought the marauding armies of both the British and Tipu Sultan. His story is full of adventure and thrill, intrigue and treachery, a case-book of bravery. The book is profusely illustrated. It was heavily researched. The surviving members of the Raja’s family were interviewed at Pazhassi and information was gathered from many books and historical records. The text in the book is but a fraction of the material actually obtained.”

[12] Aditi De’s Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and illustrated by Pooja Pootenkulam in the Great Lives series published by Scholastic India has been released this month.

[13] Gandhi: My life is my message by Jason Quinn, illustrated by Sachin Nagar. It is available in English and Hindi. The translator is Ashok Chakradhar. It is part of Campfire Graphic Novels’s Heroes Series that introduces readers to historical figures who led lives worth knowing, and whose stories are true life adventures.

[14] It is available freely for circulation since “Mahatma Gandhi cannot be any one person’s property, there is no copyright of this publication.” First edition 1997.

[15] Literature in Action is a programme started by Paro Anand that seeks to bring young people and books together.

[16] It was co-authored by her writer-son, Vikram Seth and illustrated by the late Bindia Thapar, published by Puffin India ( English) and Pratham Books ( Hindi).

[17] Published by Pratham Books

[18] In an email Nina Sabnani wrote, “Mukand and Riaz was initially an animated film that later became a book. It is a true story about my father Mukand and his friend Riaz. There were several things that brought this project together. My father told me the story of his life very late, close to his death. I wanted to share this with my siblings so I just wrote it up like a story and shared it with them and some friends. My friends persuaded me to think about it as a film. I was quite disturbed by the frequent riots in Ahmedabad that happened and me as a designer did not respond in any way. I thought it maybe my way of protesting. But protests always forget children. So I wanted to reach children. Fortunately I also received some funds at NID as students were working towards making films on the rights of children for a UNESCO Israel project, Big Small People. Since my father had repeatedly said how much he missed his best friend and how the partition separated them, I thought I would create a film that focused on the rights to home and friendship. I also had a fond hope that if the film was made and Riaz happened to see it he would contact my dad. Of course that did not happen but my father was able to see the film one week before he passed away. I used cloth because he worked in the Textile Mills and was passionate about fabric and prints.” Mukund and Riaz is published by Tulika Books.

[19] The reader shares moments with 10-year old Hina who lives in Purani Dilli, the walled city of Delhi. She comes from a family of zardozi embroiderers. This exquisite craft is, however, slowly dying as craftspeople find fewer takers for their work or are forced to compromise on care and quality to meet the prosaic demands of the times. Along the way, we get glimpses of life in Old Delhi – its lanes, its ancient mohallas which have seen the pain of Partition. Hina loves where she lives, and warm colour photographs take us right into her world. Guides for projects / discussions and a reading list are provided at the end as further avenues for exploring.

[20] To me it is an example of using history to comment on the present. It is ostensibly about the revolt (and the story calls it a revolt too whereas an uprising would be more accurate given it is written from the perspective of the adivasi), the introduction refers to the “outsiders”, the story is about the fight against the British and then it concludes with “Almost 160 years have passed since the Hul. We are alive but still not the owners of our lives? What will it take for us to be really free?” The term “outsider” is left open-ended. Ruby is the founder-publisher of Adivaani, a publishing house that focuses on producing literature for an by the adivasis.

[21] Neela: A Victory Song is published by Puffin Books India.

[22] Jamila Gavin’s Surya Trilogy is published by Egmont.

[23] Beautiful Lie was published by Bloomsbury

[24] A book review article I wrote on Partition and Children’s Literature and I interviewed Jamila Gavin and Irfan Master.

[25] The Grasshopper’s Run was first published by Scholastic India and worldwide by Bloomsbury.

[26] Dear Mrs Naidu ( 2015) is a Young Zubaan publication.

[27] Forthcoming by Pratham Books is Khwaja Ahmad Abbas’s Bharat Mata ke Paanch Roop ( The Five Forms of Bharat Mata) which are character sketches of five ordinary women whom he considered as the true faces of the Bharat Mata trope. These are originally in Urdu but have been done for us by his niece Syeda Hameed. According to Manisha Chowdhury, Editorial Head, Pratham Books “we see this as a good way to introduce the idea of subaltern narratives to children and expand the idea of history.”

[28] For instance, Saffron, White and Green: the amazing story of India’s independence; A Flag, A Song and a Pinch of Salt: Freedom Fighters of India; Puffin Lives: Mahatma Gandhi; Let’s Go Time Travelling; fictional biographies of Jahanara and Jodh Bai; a short story collection called History, Mystery, Dal Biryani and a novel called Give us Freedom and most recently the bestseller, A Children’s History of India, published by Red Turtle. Email from Subhadra Sen Gupta.

[29] There is also a book on Alluri Seetharama Raju in Telugu. He led the ill-fated “Rampa Rebellion” of 1922–24, during which a band of tribal leaders and other sympathizers fought against the British Raj. He was referred to as “Manyam Veerudu” (“Hero of the Jungles”) by the local people

[30] It explains why authors like Deepak Dalal and Nandini Nayar have been able to

[30] It explains why authors like Deepak Dalal and Nandini Nayar have been able to  write historical fiction set in 1857. Research is easy to come by. Deepak Dalal’s historical fiction set in the time of 1857 Sahyadri Adventure series – Anirudh Dreams and Koleshwars Secret. He says, “I have received good feedback about the books. Demand is ok, but nothing to thump my back about. We are into the 3rd edition now. Schools love the books and many have used them as readers. But then most of my books are picked up as readers.” Nandini Nayar’s When children make history: Stories of 1857 is a novel about two Indian children who befriend an English boy who considers India his real home. The three of them chance upon a bunch of soldiers making rotis and help them. So, basically, the novel ends with the beginning of the Uprising. In an email to me she wrote, “I wrote the book [since] I was reading a lot about 1857 and the British Raj and began thinking about how it would be if some Indian children were to befriend an English boy. “ The book was first published as an ebook, then

write historical fiction set in 1857. Research is easy to come by. Deepak Dalal’s historical fiction set in the time of 1857 Sahyadri Adventure series – Anirudh Dreams and Koleshwars Secret. He says, “I have received good feedback about the books. Demand is ok, but nothing to thump my back about. We are into the 3rd edition now. Schools love the books and many have used them as readers. But then most of my books are picked up as readers.” Nandini Nayar’s When children make history: Stories of 1857 is a novel about two Indian children who befriend an English boy who considers India his real home. The three of them chance upon a bunch of soldiers making rotis and help them. So, basically, the novel ends with the beginning of the Uprising. In an email to me she wrote, “I wrote the book [since] I was reading a lot about 1857 and the British Raj and began thinking about how it would be if some Indian children were to befriend an English boy. “ The book was first published as an ebook, then  print and has recently been translated into Malayalam by Mango Books, the children’s imprint of DC Books.

print and has recently been translated into Malayalam by Mango Books, the children’s imprint of DC Books.

[31] In an email to me.

[32] In an email to me.

[33] According to rumours that spread like wildfire, fifty-year-old Akhlaq had stored beef (cow’s meat) in his fridge. The cow is sacred to Hindus. A mob gathered and lynched him and injuring many members of the family. On 2 October 2015, two days after the incident in a village in Dadri, 35 kms from Delhi, Ravish Kumar went to report. “A Sewing Machine, Murder, and The Absence of Regret” (Published and accessed on 2 Oct 2015)

15 August 2017