Every Monday I post some of the books I have received in the previous week. Embedded in the book covers and post will also be links to buy the books on Amazon India. This post will be in addition to my regular blog posts and newsletter.

In today’s Book Post 7 I have included some titles that I received in the past few weeks and are worth mentioning and not necessarily confined to parcels received last week.

Enjoy reading!

27 August 2018

Every Monday I post some of the books I have received in the previous week. Embedded in the book covers and post will also be links to buy the books on Amazon India. This post will be in addition to my regular blog posts and newsletter.

In today’s Book Post 6 I have included some titles that I received in the past few weeks and are worth mentioning and not necessarily confined to parcels received last week.

Enjoy reading!

20 August 2018

Religion, more or less, arises out of divine wreckage. And science, too — religion’s estranged half sibling — addresses itself to such animal dissatisfactions. In The Human Condition, writing in the wake of the Soviet launch of the first space satellite, Hannah Arendt reflected on the resulting sense of euphoria about escaping what one newspaper report called “men’s imprisonment to the earth.” This same yearning for escape, she wrote, manifested itself in the attempt to create superior humans from laboratory manipulations of germ plasm, to extend natural life spans far beyond their current limits. “This future man,” she wrote, “whom the scientists tell us they will produce in no more than a hundred years, seems to be possessed by a rebellion against human existence as it has been given, a free gift from nowhere ( secularly speaking), which he wishes to exchange, as it were, for something he has made himself.”

Religion, more or less, arises out of divine wreckage. And science, too — religion’s estranged half sibling — addresses itself to such animal dissatisfactions. In The Human Condition, writing in the wake of the Soviet launch of the first space satellite, Hannah Arendt reflected on the resulting sense of euphoria about escaping what one newspaper report called “men’s imprisonment to the earth.” This same yearning for escape, she wrote, manifested itself in the attempt to create superior humans from laboratory manipulations of germ plasm, to extend natural life spans far beyond their current limits. “This future man,” she wrote, “whom the scientists tell us they will produce in no more than a hundred years, seems to be possessed by a rebellion against human existence as it has been given, a free gift from nowhere ( secularly speaking), which he wishes to exchange, as it were, for something he has made himself.”

A rebellion against human existence as it has been given: this is as good a way as any of attempting to encapsulate what follows, to characterize what motivates the people I came to know in the writing of this book. These people, by and large, identify with a movement known as transhumanism, a movement predicated on the conviction that we can and should use technology to control the future evolution of our species. It is their belief that we can and should use technology to augment our bodies and our minds; that we can and should eradicate aging as a cause of our death; that we can and should use technology to augment our bodies and our minds; that we can and should merge with machines, remaking ourselves, finally, in the image of our own higher ideals. They wish to exchange the gift, these people, for something better, something man-made. ( p.2)

….

In philosophy of mind, the notion that the brain is essentially a system for the processing of information, and that in this it therefore resembles a computer, is known as computationalism. As an idea, it predates the digital era. In his 1655 work De Corpore, for instance, Thomas Hobbes wrote, “By reasoning, I understand computation. And to compute is to collect the sum of many things added together at the same time, or to know the remainder when one thing has been taken from another. To reason therefore is the same as to add or subtract.”

And there has always been a kind of feedback loop between the idea of the mind as a machine, and the idea of machines with minds. “I believe by the end of the century,” wrote Alan Turing in 1950, “one will be able to speak of machines thinking without expecting to be contradicted.”

As machines have grown in sophistication, and as artificial intelligence has come to occupy the imaginations of increasing numbers of computer scientists, the idea that the functions of the human mind might be stimulated by computer algorithms has gained more and more momentum. In 2013, the EU invested over a billion euros of public funding in a venture called the Human Brain Project. The project, based in Switzerland and directed by the neuroscientist Henry Markram was set up to create a working model of a human brain and, within ten years, to simulate it on a supercomputer using artificial neural networks.

( p.55-56)

Wellcome Book Prize 2018 winner Mark O’Connell’s To Be a Machine: Adventures Among Cyborgs, Utopians, Hackers, and the Futurists Solving the Modest Problem of Death is an incredible account of the journalist’s investigation into what is transhumanism and who are these people actively engaged in this movement, in their search for the Holy Grail of longevity with the help of technology. It is an astonishing book for the amount of research involved, the innumerable meetings, the conferences attended, ideas shared, all of which are pretty amazing given that money is being poured into researching this niche area of how the human life span can be increased. It it is the underlying, very human, deep fear of death that is propelling this research forward with entrepreneurs like Peter Thiel also involved in funding these activities. There are famous centres like the centre maintained by the Alcor Life Extension Foundation which is experimenting with cryogenics in keeping humans “alive”.

In this interview with The Irish Times, Mark O’Connell says “Transhumanism really is for me the displacement of yearnings and anxieties that have traditionally been the preserve of religion. But, overwhelmingly, that’s a sore point for transhumanists. They see themselves as the heirs to enlightenment. In their kind of hyper-rationalist thinking, any notion of spiritualism or mysticism is a complete anathema.”

In another interview with The Verge he says “When you talk to transhumanists, in one way or another, they all aspire to knowing everything and to being gods basically. And I just sort of thought, this is actually something I can’t relate to at all. The idea of being that all-powerful and omnipresent, it’s almost indistinguishable from not existing and I can’t quite justify that.

They’d say, you’ve got Stockholm syndrome of the human body. But that kind of idea is very unappealing to me. I can’t see why that would be your idea of your ultimate human value. I was always trying to come to grips with these ideas and come to grips with what it meant for these people to be post-human, and just wind up getting more confused about what it meant to be a human at all in the first place. I can identify with wanting to not die, but I can’t with wanting to live indefinitely.”

It is a surreal world that the transhumanists believe in, with almost an evangelical fervour for defeating mortality. The reason Mark O’Connell embarked upon this quest of his was because he had become a father for the first time and suddenly questions of mortality and death became very real. ( On a related note. Here is a superb article in The Paris Review of Mothers as Makers of Death by Claudia Dey, 14 August 2018.) But he is very clear, even after one a half years of research for this book, that he will never be a cyborg or a transhumanist. A fact he reiterates in the book as well as in an interview to The Millions. His deep dive in to the subject makes him an expert in the field so he recommended five books to understand transhumanism for The Guardian too (10 May 2018).

Whether you agree or not with the transhumanists, To Be a Machine must be read to understand how man is pushing the known boundaries of knowledge using technology to try and find an answer to the eternal question “How to overcome mortality?”. It is like reading science fiction except that all that is written in the book is very real — very real people, very real experiments in very real facilities. For now it may seem like a fanciful playground of a bunch of well-funded individuals ( mostly male) who may or may not find their Holy Grail, but a possible offshoot of this innovative research may have other more practical applications. Who knows?! Only time will tell.

To buy the book published by Granta on Amazon India:

17 August 2018

Strongmen is a slim book, a collection of fables about strong men. As the book blurb says “Eve Ensler, the American playwright (The Vagina Monologues), goes beneath the skin – or should we say orange hair – of US President Donald Trump. Danish Husain, the Indian storyteller and actor, finds himself telling us the story not only of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi but also of the ascension of the extremism of the Sangh Parivar. Burhan Sönmez, the Turkish novelist, ferrets about amidst the bewildering career of the Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Ninotchka Rosca, the Filipina feminist novelist, unravels the macho world of Rodrigo Duterte. Their essays do not presume to be neutral. They are partisan thinkers, magical writers, people who see not only the monsters but also a future beyond the ghouls. A future that is necessary. The present is too painful.”

Strongmen is a slim book, a collection of fables about strong men. As the book blurb says “Eve Ensler, the American playwright (The Vagina Monologues), goes beneath the skin – or should we say orange hair – of US President Donald Trump. Danish Husain, the Indian storyteller and actor, finds himself telling us the story not only of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi but also of the ascension of the extremism of the Sangh Parivar. Burhan Sönmez, the Turkish novelist, ferrets about amidst the bewildering career of the Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Ninotchka Rosca, the Filipina feminist novelist, unravels the macho world of Rodrigo Duterte. Their essays do not presume to be neutral. They are partisan thinkers, magical writers, people who see not only the monsters but also a future beyond the ghouls. A future that is necessary. The present is too painful.”

With the permission of the publisher here is an extract from Eve Ensler’s essay:

This is the story of what happened in the late time, right before the end time, that later got interrupted and became the new time. In those days there arrived in the land of violent amnesia and rapacious dreams – a virus. It first became discernible in an oafish, chubby man with orange hair. Some say it was the virus that turned his hair orange. Others claimed his hair was actually the virus. The oafish, chubby man with orange hair goes on to become the most powerful man in the world.

It was highly debated whether the intensity of the infection was the cause of his rise, but it has since become clear that the virus was a very contagious one and that much of the populace had a dormant strain of it lodged in their beings which was activated by the orange man during his toxic campaign.

Those infected the most deeply were those with unexamined wounds and openings from childhood, repressed fear, insecurities that were ripe for othering and rage, predisposition towards racism and sexism and insatiable daddy hunger. These tendencies were exacerbated and catalyzed by the way the portly, thuggish leader injected the virus into the unsuspecting crowds through angry white-hate filled spittle, slimy superlatives, sham filled promises, and toxic red caps which allowed the virus to seep in through the hair follicles and head. Bald men were most susceptible.

This, fortunately, was not true of all segments of the population because some appeared to have built-in immunity. Most of those were the ones who lived on the various edges, which was ironic, as it was the ones most foreign and exiled from the culture who would eventually find a cure. We will come to that later.

It was also highly debated whether the man with orange hair was the origin of the virus or simply the manifestation of it. Some said it didn’t matter, but I believe it matters a lot. For if the chubby man were the originator of the virus, then it would have simply been one sick individual contaminating the public and if and when he was eliminated, the virus, would, in theory, be gone as well. But we know this didn’t happen. So the question then evolved: why was the oafish, portly man with orange hair the major host of the virus?

And again, the theories abound.

One classic theory is that the thuggish man had become what no one had yet become in the time of late date consumption and greed. He had evolved or devolved (depending on your perspective) into what the psychologists later came to define as a genocidal narcissist – a person willing and able to destroy everyone and everything on the planet as long as it makes him feel momentarily better. That extreme and total endgame narcissism made the oafish man a perfect super host for the virus. For it has since been discovered that the virus can only fester in an environment where the host has developed no antibodies to tolerate others, or indeed criticism, difference, curiosity, questions, doubt, ambiguity, the truth, mystery, waiting, thinking, reading, reflecting, questioning, wondering, caring, feeling, listening, or studying. It is where the healing properties of humour and irony have been killed off and self-obsession, revenge and self-adulation have taken their place.

Noted symptoms of the virus are: hysteria, mania, illogical thinking, impulse disorder, bullying, a distorted belief that the group and gender you belong is superior, vile and show-offy compulsive grabbing, molesting behaviour towards women, compulsive lying, increased paranoia, loss of ability to distinguish between good and evil (for example equating Nazi and white supremacist with people fighting for their constitutional rights) and shifting and constantly evolving enemies, because the infection needs a target to energize its effective components. One day it was Mexicans, the next day blonde women reporters, the next a Puerto Rican mayor, the next Black football players. It was actually irrelevant to the virus who the enemy was as long as it kept shifting and escalating as the pathogen craved and fed off this antagonistic energy. But it has been conclusively determined that the virus would first seek already existing weaknesses in the DNA of the culture.

Also read an interview with Eve Ensler with Vinutha Mallya, published in Pune Mirror.

14 August 2018

It is an uncanny coincidence that today two seminal articles have been published online analysing journalism as we know it today and its complicity with the powers that be even if it means resorting to unethical practices and compromising their positions. Both articles are by reputed journalists. The first is by Rafia Zakaria in the Baffler called “Stalking the Story” or what she sees as the calling card of predator journalists. The second is by Suchitra Vijayan as a part of The Polis Project called “Journalism as Genocide” tracking hate speeches, fake news etc as propaganda tools to ultimately result in hate crimes such as genocide or other forms of violence like lynchings and the attempted assassination attack on student activist Umar Khalid.

articles are by reputed journalists. The first is by Rafia Zakaria in the Baffler called “Stalking the Story” or what she sees as the calling card of predator journalists. The second is by Suchitra Vijayan as a part of The Polis Project called “Journalism as Genocide” tracking hate speeches, fake news etc as propaganda tools to ultimately result in hate crimes such as genocide or other forms of violence like lynchings and the attempted assassination attack on student activist Umar Khalid.

Umar Khalid

Posted by Nadeem Khan on Monday, August 13, 2018

Rafia Zakaria says in her concluding remarks:

The predator journalist is a creation of the War on Terror, whose narrative requires all that is Western to be anointed while everything else is reduced as a tool in service of it. The journalist who sets out to “unravel” its mysteries is thus as much a warrior in service of this narrative as the soldier who visibly enacts its agenda. All this would at least be less objectionable if it were owned and admitted, if those searching for rape stories among Yazidi women or taking pictures of women attending secret schools did not pretend to be journalists or aligned with a code of ethics that requires consent of subjects, respect for their humanity, and a commitment to confidentiality.

The lethal aspect of the predator journalist is the pretense, the implication to readers that they are in fact “objective,” bound by ethics, even when no such moral restraint inhibits their actions. This is a debasement of the idea of truth, now reduced to an outmoded goal of journalisms past, whetted by a now-debunked idealism. The remainder is a crass predation, a reduction of insight to access, and deeply reported stories to orchestrations of pressure and predation on hapless subjects. In the theater of the War on Terror, the United States need no longer send predator drones; it can avail the talents of predator journalists, whose sly shape-shifting is a much sleeker and at times a more lethal weapon.

Suchitra Vijayan says:

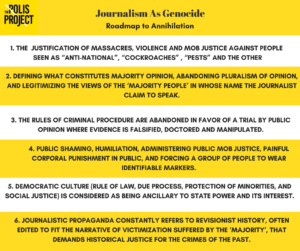

Upon analyzing witness testimonies from the Nuremberg, Yugoslavia and Rwanda trials, two things become increasingly clear. First, truthful reporting of facts, analytical investigation of issues, and a stand against violence by journalists in all these instances could have both changed the behavior of the perpetrators, and in some instance even prevented the slaughter. Second, when airwaves become a platform for ideological, socio-religious-nationalist populism, there are clear roadmaps with milestones and perfected patterns of hate that lead to eventual violence and destruction of a society. Some of these milestones include:

While the list enumerated above is a repetitive pattern of behavior gathered from over hundred witness testimonies from Nuremberg to Rwanda, their relevance resonates for India today, as we are birthing a new dystopia of hate and bigotry. This list holds up a haunting mirror to the ugliness on display and the vileness employed by some Indian news channels, anchors, and journalists. It is as much a war over the minds of the people, as it is a war to enact extrajudicial and unconstitutional laws that encroach into and legislate the private lives of citizens. The absolute essence of this priming is the stamping out of pluralism in all its forms – pluralism of ideas, opinions, faiths, beliefs, memories, myths and even gods.

…

Sudhir Chaudhary, editor, Zee News, in an interview to Outlook magazine stated that: “It has become necessary for media houses to take a stand on certain issues. It has to be a nationalistic approach. That benefits the people of India. What do you call neutral and secular? No one is neutral anymore. I will pitch for a nationalistic reporting, …” He further states, “If you want to live in India and want the breakup of India, then why do you want to live here? Leave the country and go.”

What happens to journalism when it willingly wraps itself in a flag? To borrow from Adorno it facilitates a politics of murder and destruction.

While nationalism will continue to mediate many facets of our life, it cannot become the prism through which we understand the complexities of the world. Chaudhary, and many like him, hold an immense power of persuasion and present a position of unthinking hawkish nationalism that uncritically propagates a retreat to banal patriotism. This excludes the possibility of criticising the state and its political projects. Journalism is not the witch’s brew from Macbeth, and journalists cannot become the agents of chaos and conflict. Journalism demands detachment and objectivity that allows for dissent, disagreement, and freedom of expression. In the absence of such ethics, it clears the ground for violence and does a great disservice to the democratic way of life.

While handing down its judgment in the media trial, the ICTR rightly criminalized the hate speech of a powerful media against a vulnerable minority. The great fight for individual humanity against crimes by the state – and the journalists who defend it – has to begin with accountability. To rephrase what Rwandan journalist Thomas Kamilindi testified at the war crimes’ tribunal, how should we hold journalists accountable for their actions, and if need be prosecute them, if they knowingly caused harm, and incited violence. We must find a way to articulate and respond to such abuses of power without violating the principles of freedom, which are an indispensable cornerstone of democracy.

14 August 2018

Before She Sleeps is Pakistani writer Bina Shah’s fifth novel. ( On Twitter: @binashah ) It is about an “illegal” commune of women who reside in an abandoned warehouse on the outskirts of Green City. Their space is called Panah which in Persian means shelter. These women are led by a leader, Lina, and only appear under the cover of darkness. They survive by paying their bills in cryptocurrency with purchases usually made on the black market. Their business is to offer platonic cuddles to male clients in Green City but it is all to be kept under wraps otherwise the “Agency” will hunt them down. The story revolves mostly around twenty-four-year-old Sabine who has been living in Panah since she was seventeen.

The premise for Before She Sleeps is so plausible since it seems much of it already exists if we search long and hard. None of this is really fiction, it’s only pushing the boundaries of truth or reality as we know it today a little further. The Panah can be a metaphor for the silent community women tend to form together even in the most public of spaces with one or two looked up to as guides/mentors. This bonding happens amongst strangers too. Sometimes it is fleeting, sometimes more permanent. Though the dark side of the viciousness of women towards other women too exists.

The relevance of Before She Sleeps with references to “rare whales and giant turtles that had been cloned back into existence”. More so given recent news coming in of 40,000-year-old worms being revived to life. Or “All beef, eggs, in fact anything natural, is created in a lab with synthetic polymers, proteins, DNA.” as news trickles in of meat being manufactured in labs.

Yet the further one reads Before She Sleeps the sense that the story is an excuse for the author’s personality and beliefs that run deep through, definitely more in this book than any of the previous novels Bina Shah wrote. Before She Sleeps will become her transitional work in her oeuvre in time to come. It’s the channelling of herself into a new kind of writer, one who does not abandon her past but looks ahead firmly taking along with her all the recent socio-political experiences accrued. The gender violence evident in the discrimination towards women (otherwise why would there be such a shortage of women in the city?), the persistent patriarchal constructs of social rules of engagement, the very recognisable authoritarian figures in most of the male characters even the nameless ones like Rupa’s “father” who tries to rape her are symptomatic of her simmering rage against the horrors that perpetrated towards women continuously. There is undeniably something different in this novel as compared to her early works. Take for example the section on recipes. “When I found the cookbook, it’s spidery, ethereal handwriting already fading from the pages, I wanted desperately to save it’s contents, if not it’s form. Our mothers, aunts, grandmothers live only in representations of their lives as we, their daughters, try to re-create them.” This is not an off-the-cuff observation by a novelist but it is a sharp observation by Bina, the woman, the thinker, the opinion maker, who has been mulling on this truth for a very long time. In her correspondence with me, Bina Shah says “Unfortunately I think what caused that beyond a doubt was the assassination of my friend Sabeen Mahmud. Suddenly everything because so much more intense, grief-filled, and serious, when I was writing the novel back in 2015. I poured all my emotions about her death – anger, grief, fear, helplessness – into the book, into Sabine’s thoughts.”

Before She Sleeps is an important addition to the rapidly expanding science fiction literature from South Asia and increasingly from the Middle East.

*****

Bina Shah has recently become a regular contributor to the International New York Times. She is a Pakistani writer who is a frequent guest on the BBC. She has contributed essays to Granta, The Independent, and The Guardian and writes a monthly column for Dawn, the top English-language newspaper in Pakistan. She holds degrees from Wellesley College and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and is an alumna of the University of Iowa’s International Writers Workshop. Her novel Slum Child was a bestseller in Italy, and she has been published in English, Spanish, German and Italian. A Season for Martyrs is her U.S. debut. She lives in Karachi.

A regime doesn’t want witnesses to its horrors, and diaries and journals are specific forms of resistance. I was thinking of the diary of Anne Frank, but also the diary that Malala Yousufzai kept under the Taliban and published in the BBC as Gul Makkai. They are historical records as much as personal accounts, and most authoritarian regimes don’t want evidence of the crimes they’ve perpetrated on their victims.

2. How and why did you start thinking of Before She Sleeps especially when the modern classic The Handmaid’s Tale continues to be published and now exists on television too?

I wrote a short story called “Sleep” which became the first chapter of my novel, back in 2006. I added to it until it became about 100 pages long. Then I left it in a drawer, thinking it was a ridiculous premise and I couldn’t execute it. I took the short story to a literature festival in Copenhagen in 2013, and when I read it to the audience, the poet Warsan Shire, who was also there, told me that I had to turn it into a novel. I listened to her, and started working on it in 2014, long before the television series came out. The Handmaid’s Tale was not much of an influence on my work. 1984 by George Orwell was much more on my mind in the devising of such an authoritarian regime. But also the dictatorships that I have lived under in Pakistan, and those of secular dictators in Middle Eastern countries, as well as repressive Islamist regimes in Iran and Saudi Arabia.

3. Isn’t this novel quite a shift for you in the stories you select to tell though the strong women remain the focal point?

It’s a change in genre which was risky and quite frightening for me as a writer. It’s easier and more comfortable to stick with what you have always been doing. But it represented a huge challenge and I decided to give it a try.

4. Has your maintaining the Feminstani blog and writing for papers like The New York Times informed your writing style for novels? Do you notice a shift in the way you present material?

I don’t write the same way in a novel as I do in my blog or my journalism. The writing I do for fiction is more poetic, more musical, more laden with references to other texts, literary (poetry and prose), artwork, religion (there are Quranic references, influences from Sufism, Islamic philosophy), and politics and history. It’s much more creative than my blog or my journalism can ever be.

5. “My fear is an animal I can’t hide”. Isn’t this true of all women?

It’s true of all humans sometimes.

6. Why choose the first person narrative to tell this story for Sabine and third person for the others?

Only Sabine has the first person narrative and that is to make you feel more close to her. It’s more intimate. The others are all told in third person. I wanted to distinguish Sabine from the other narrators, make you feel more invested in her story. I needed both men and women to lend their voices to this narrative, to show the effects of the regime on both genders. I’m making the argument that a world without the female gender is an unbalanced world, and hurts everyone. Most proponents of male domination don’t seem to understand that at all.

7. Is this your first spec-fic book? How did you invent terms like “currency stick”, genetic switch chips, virtual tunnels on the Deep Web, memory slips, and thought-to-device to name a few innovations mentioned?

It’s my first speculative fiction, dystopian book. I never imagined I’d write one. I made up those technologies that you mention. Others, like lab-made meat, or cloned animals, seemed a logical extension of the science we have already, although I did write about them long before they came into the news.

8. How much research this novel require?

A lot! I did a lot of research on the science, since several of the main characters are scientists. I also researched the geographical area I was writing about. I travelled to Dubai several times to observe the landscape, the buildings. And I was caught in a huge dust storm the likes of which I’ve never seen in my life. It appears in a seminal scene in the book as a kind of deus ex machina.

9. “Sometimes I’m seized by sorrow at the position we’re all in, how fragile our inner safeguards against the betrayals that can happen to us in many ways, internal and external.” Why do I get the impression that this is a lament by Sabine not just for the immediate story but by you as well at a larger level too?

It seems a fairly self-evident observation about the world. I’m sure all of us have felt this way at least once in our lives.

10. What is the short story that this novel grew out of? Is it available online?

No, it’s not available online, it was only published in Denmark by a boutique publisher in a very limited edition. Sorry – but this one is miles better!

Buy the hardback and Kindle edition on Amazon India.

14 August 2018

Sometimes it is impossible to “review” a book except to say “Read it”. Oliver Sacks The River of Consciousness is a fine example of this. It is a collection of his essays on diverse topics but with one objective — how does the brain work? How does it process? How does it affect memories? What is true and what is false? What is a figment of our imagination? What does science reveal? This is precisely the

Sometimes it is impossible to “review” a book except to say “Read it”. Oliver Sacks The River of Consciousness is a fine example of this. It is a collection of his essays on diverse topics but with one objective — how does the brain work? How does it process? How does it affect memories? What is true and what is false? What is a figment of our imagination? What does science reveal? This is precisely the  fundamental argument Siddharth Mukherjee makes in his Laws of Medicine TED talk. Irrespective of all the advancements in technology, it is the brain which remains the most important for the speed at which it analyses and processes information, constantly pushing known boundaries to discover new frontiers of knowledge that are so far unimaginable.

fundamental argument Siddharth Mukherjee makes in his Laws of Medicine TED talk. Irrespective of all the advancements in technology, it is the brain which remains the most important for the speed at which it analyses and processes information, constantly pushing known boundaries to discover new frontiers of knowledge that are so far unimaginable.

The River of Consciousness is a posthumous publication but in it is much food for thought. Whether it is discussing creative energies to how the brain works while analysing information as in the case of Charles Darwin or even how do children learn and process information are fascinating points to ponder upon. For instance Prof. Sacks says “Children have an elemental hunger for knowledge and understanding, for mental food and stimulation. They do not need to be told or ‘motivated’ to explore or play, for play, like all creative or proto-creative activities, is deeply pleasurable in itself.”

The River of Consciousness is an excellent book to possess and to return to often too.

To buy The River of Consciousness ( On Kindle ; Paperback ; Hardcover)

14 August 2018