Interview with Daisy Rockwell regarding her translation of Khadija Mastur’s “Aangan” / “The Women’s Courtyard”

Daisy Rockwell is a painter, writer and translator of Hindi and Urdu literature living in the United States. Her translations include Falling Walls, by Upendranath Ashk, Tamas, by Bhisham Sahni, and The Women’s Courtyard by Khadija Mastur. Her recent translation of The Women’s Courtyard is fascinating since it comes across as a very confident translation as if fiction about women and their domestic spaces is completely acceptable. A translation of the very same novel done nearly two decades earlier is equally competent but for want of a better word, it is far more tentative — at least reading it now. When I first read the translation of Aangan in 2003 it did not feel amiss in any manner but today comparing the two translations it is as if Daisy Rockwell’s translation of The Women’s Courtyard is imbued with a strength influenced by popular sentiments which is in favour of women particularly in the wake of the #MeToo movement. It may not have been done consciously by Daisy Rockwell but it is evident in the tenor of the text. The Women’s Courtyard is a pleasure to read.

I interviewed Daisy Rockwell via email. Here are excerpts:

1. Why did you choose to translate Aangan?

A friend had suggested I read it because of my interest in literature of that period and I was also shifting my attention to novels written by women. I was struck by the delicate, clean prose and the complex portrait Mastur painted of a young woman’s life.

2. How long did it take to translate and edit the text? I wonder how many conversations you must have had with yourself Daisy while translating the book?! Or was it just a task to be finished in time?

I don’t think frankly that anyone is usually sitting around impatiently waiting for one’s translation of a classic literary work. My deadlines are all my own. A project of that size usually takes about a year. I usually set myself a daily page quota which I don’t always meet. I had many conversations with myself about this book, and continue to do so. One of the great strengths of Mastur’s novels is that she doesn’t ever reveal everything. One is left pondering and questioning for a long time after. I still have questions that I can’t answer, and that I keep turning over in my mind. Translation issues less so than thoughts about Aliya’s interior universe and motivations.

3. While translating the text did you refer only to the original manuscript or did you constantly read other translations and commentaries on the text?

I consulted heavily with my friend Aftab Ahmed, who is also a translator, and who grew up in the same general area where the novel is set. I would check his responses with the previous translation in English when I was unsure of what was being said. Retranslation is interesting because the previous translation gives you an interlocutor. Even if you don’t agree with the choices the other translator(s) made, you learn to look at words and sentences from a different perspective if you are stuck on something confusing. Every translation is different, word for word, paragraph for paragraph, so sometimes just rearranging things jogs one’s ability to understand. Mastur’s style is not that difficult in terms of grammar, but there are historical items that are hard to find dictionary definitions for and that I had to research. Usually it has to do with terms for items of clothing or architectural details.

4. Do you feel translating works from Hindi/Urdu into English involves a translation exercise that is very different to that of any other language translation?

I think there would be parallels from translating into English from other South Asian languages. A big challenge is that the syntax is the opposite—English is what is known as a ‘right-branching language’ syntactically. Indic languages are left-branching. This is also true of Japanese. When the syntax has to be flipped it can be a challenge, because sometimes that syntactical difference can even be reflected at the paragraph level and one has to switch the order of some of the sentences in the paragraph. Indic languages also tend to have many impersonal constructions whereas English prefers active verbs and subjects. Think of ‘usko laga jaise…’ as opposed to ‘she felt as though…’. Because of this one has to continuously change voice without trampling on the original meaning.

5. Why did you translate the title “Aangan” as “The Women’s Courtyard” when the literal translation of “Aangan” is “inner courtyard”?

The translation of the title is ultimately up to the editor and the publicity team. I get to veto options I dislike, but ultimately they choose the title based on concerns that are sometimes outside of the translator’s purview. “Aangan” couldn’t be called ‘The Inner Courtyard’ because that is the title of the previous translation and they wanted to distinguish them. An ‘aangan’ is not technically just for women, but in this context, it is the domain of women. I assume they added in ‘women’s’ to invoke the importance of women’s experiences to the novel.

6. While translating Aangan did you choose to retain or leave out certain words that existed in Urdu but did not use in English? Is this a conundrum that translators often have to face — what to leave and what to retain for the sake of a clear text?

AK Ramanujan, with whom I was fortunate to take a graduate seminar on translation shortly before his death, pointed out to me that in a long novel you have the opportunity to teach the readers certain words. I take this as my maxim and add to it the notion that you cannot teach them many words, only a few, so you must make a choice as to what you are going to make the readers learn and grow accustomed to. There has been some discomfort with the fact that I translated many kinship terms into English and left only a few of the original terms. I did this because there are way more kinship terms in literature by men than in literature by women. Kinship terms are all ‘relative’ in the sense that one person’s bahu is another person’s saas is another person’s jithani is another person’s bari mausi. If all these are left in and no one has any given names it is extremely perplexing to readers who do not know the language fluently. I will often leave a word in and teach it by context but not refer to that person by myriad other kinship terms. For example the main character’s mother could be ‘Ma’, or ‘Amma’, but I am not going to give the mother all her other kinship terms because that’s too much to ask. I want the reader who knows no Hindi or Urdu to feel comfortable enough to keep reading the book. Adding a glossary of terms doesn’t really help because most people don’t sign up for a language and kinship lesson when they pick up a novel to read. Readers that do know these terms fluently tend to speak a style of English in their homes that incorporates the Hindi and Urdu kinship terms, so they think of these as a part of Indian English, but it’s not at all the case for Tamil speakers or Bangla speakers, who all have their own kinship terms that they use in English. My goal is to create a translation that can be enjoyed by people not just in India and South Asia, but all around the world. It’s a tricky business but I attempt to cater to everyone as much as I can.

My policies on what to leave in the original language are not created on behalf of readers who are fluent in these languages, but for people who are not. My Bangladeshi friends, for example, do not know what the words saas and bahu mean. We have these words in English—mother-in-law and daughter-in-law–so I translate them. An example of a word I did not translate was takht. A takht is a platform covered with a sheet where family members sit/sleep/gather/eat/make paan, and generally do everything. I decided that this was a word the readers would need to learn from context. Why? Because it occurs on almost every page, is the center of the action, and most importantly, it has no English equivalent.

7. How modern is your translation of Aangan? For instance did you feel that the times you were translating the novel in where sensitivity and a fair understanding of women’s issues exists far more than in it ever did in previous decades helped make your task “easier”?

I try to inhabit a linguistic system that is non-anachronistic when I translate the voice of a novel. I did not use #metoo-era language, I used a more formal register and kept it less modern. I think infusing the language with a contemporary sensibility would ruin the finely drawn portrayals in the original text.

8. In your brilliant afterword you refer to the first English translation of Aangan done by Neelam Hussain for Simorgh Collective and later republished by Kali for Women/ Zubaan. Why do you refer to your translation as a “retranslation” and not necessarily a “new translation”?

No particular reason—I guess I think of them as the same thing. If I say ‘retranslation’ I am nodding to the hard work done by the path-breaker. The first translation will always be the hardest one.

9. You are a professional translator who has worked on various projects but have also translated works by women writers. What has been your experience as a translator and a woman in working on texts by women writers?

I have translated this novel by Khadija Mastur as well as her later novel, Zameen (earth); my translation of Krishna Sobti’s most recent novel is soon to come out from Penguin India’s Hamish Hamilton imprint as A Gujarat Here, A Gujarat There. I am working on a translation of Geetanjali Shree’s 2018 novel Ret Samadhi (tomb of sand) and Usha Priyamvada’s 1963 novel Pachpan Kambhe Lal Divarein (fifty-pillars, red walls).

When you translate a text, you spend way more time on it than most other people ever will, sometimes including the author him or herself! I got tired of translating patriarchy, misogyny and objectification of women, which are all par for the course in men’s writing. For the past year, I have mostly stopped reading male authors at all, because the more I read and translate women, the lower goes my tolerance for the male gaze. We don’t realize how we’ve been programmed to accept objectification and silencing of women in men’s writing until we stop reading it. It has been very fulfilling translating these fine works by women and inhabiting the detailed layers of female subjectivity that they offer readers.

10. Do you think that the translation in the destination language must read smoothly and easily for the reader or should you be true to the original and incorporate in your translated text as far as possible many of the words and culturally-specific phrases used in the original text?

I think I partially answered this above, but I do not believe that a translation should be so difficult or “under-translated” that a reader puts it down out of frustration. Difficulty and cultural specificity in the original text suffuses many aspects of the writing and is not limited to certain pieces of terminology.

| 11. The explosion in translated literature available worldwide now has also coincided with the rise of technological advancements in machine translation and neural networks. Thereby making immediate translations of online texts easily available to the reader/consumer. Do you think in the near future the growth in automated translation will impact translations done by humans and vice versa? How will it affect market growth for translated literature? |

To be honest, machine translation is horribly inaccurate because it misses nuance and does not understand human experience, culture or history. I do not believe that AI will ever replace human translators, at least when it comes to literature.

[ JBR: Interesting since I have come across arguments that say making texts available is the only factor that matters. Nothing else. This is where Google ‘s neural technology is breaking boundaries. But I agree with you — the human brain will continue to be the supercomputer. It’s a beauty!]

3 January 2019

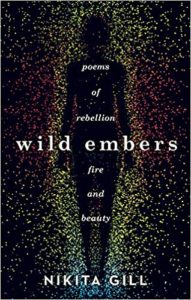

of strong, independent, and thinking women characters especially in the retelling of the age-old fairytales. In fact Fierce Fairytales was whisked away by my young daughter as her own! I was a little surprised at her action as I was not sure how much of the poetry she would understand. Yet she surprised me pleasantly by getting the gist of the stories. She may not have got the layered meaning but she got the gist. It speaks volumes of Nikita Gill’s skill as a poet to be able to connect across generations. Unsurprisingly she has a legion of followers on social media:

of strong, independent, and thinking women characters especially in the retelling of the age-old fairytales. In fact Fierce Fairytales was whisked away by my young daughter as her own! I was a little surprised at her action as I was not sure how much of the poetry she would understand. Yet she surprised me pleasantly by getting the gist of the stories. She may not have got the layered meaning but she got the gist. It speaks volumes of Nikita Gill’s skill as a poet to be able to connect across generations. Unsurprisingly she has a legion of followers on social media: