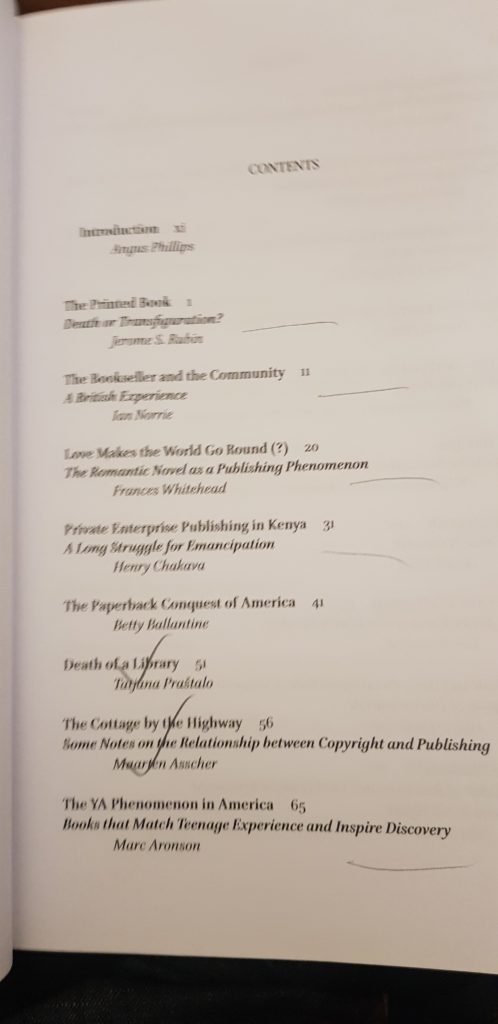

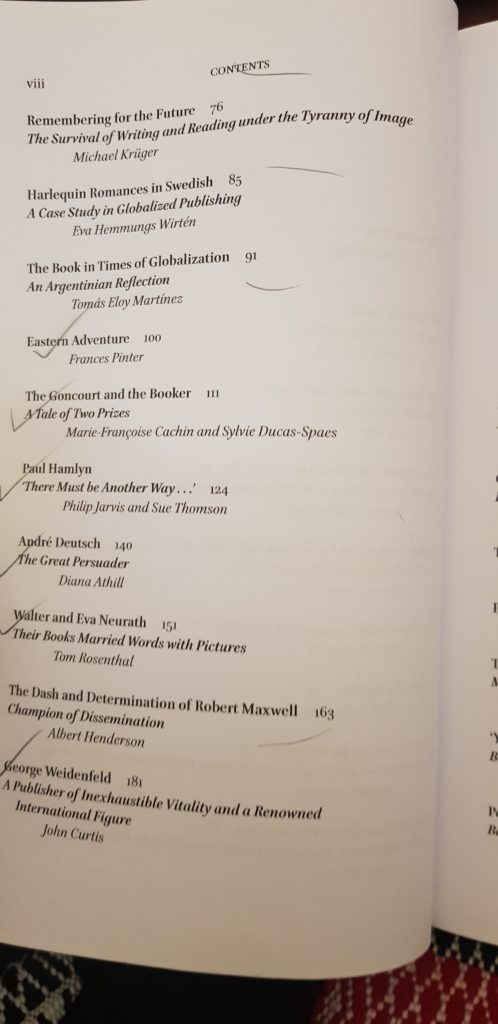

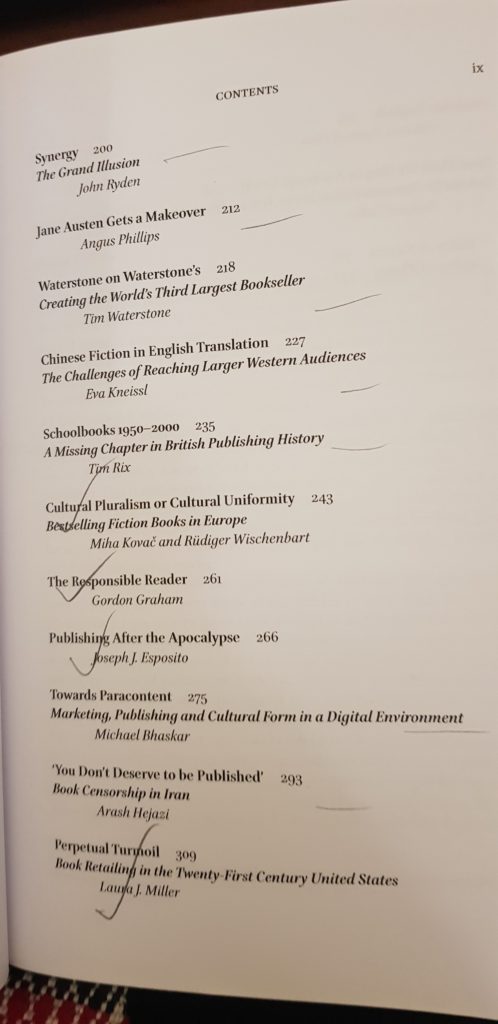

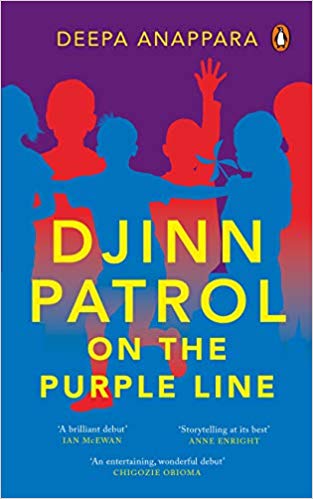

“The Cottage by the Highway and Other Essays on Publishing: 25 Years of Logos” Edited by Angus Phillips

The cheapening of information has been accompanied by the decline of copyright, the symbol of the writer’s ownership and instrument of his and the publisher’s protection. Readers are no longer wooed so much as assayed. This should give them more power. However, the increase in volume and accessibility of words has led to a decline in the art of readership. Millions of readers are oblivious to both their power and their responsibility. We need a movement for more responsible readership.

…

Reader Responsiblity is not dependent on education or intellect. Everyone reads, and everyone can exercise responsibility according to his will and capacity. Responsible reading it in the endthe only way to filter the best out of the computer-generated mass of information, to discipline distorted reporting, careless reasoning, special pleading, tendentious arguments and vulgar expression, all of which are more common in communications today than they were twenty or thirty years ago.

In simpler terms, there is a need to increase quality and reduce quantity. The reader has power to influence this.

Gordon Graham “The Responsible Reader”, Logos 21/3-4, 2010, 9-12

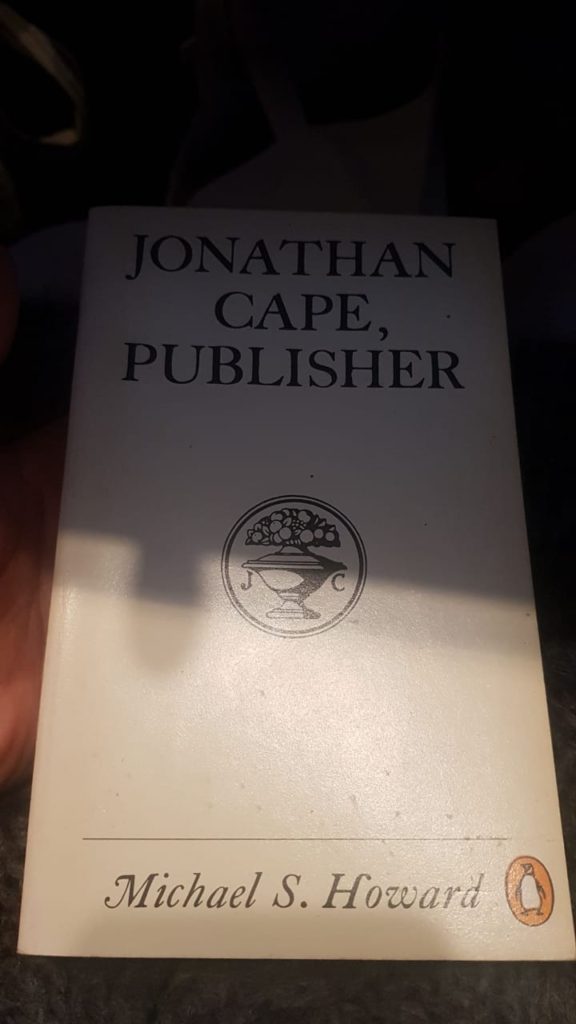

Logos is a highly reputed journal on publishing that was begun by the legendary publisher, Gordon Graham. He had founded the Logos journal in 1990, upon his retirement from Butterworths where he had served as Chairman and Chief Executive since 1974. Before this Gordon Graham worked at McGraw-Hill, as International Sales Manager in New York, and later ran the company’s book business in Europe and the Middle East. But he had also done a long stint in India with the company. Gordon Graham ran the journal successfully for many years. He had some of the best publishing professionals of the world contribute articles, interviews and book reviews. He had a vision to create an excellent platform where ideas and experiences about the publishing world could be shared and discussed. He began this initiative in the days before email and smartphones were even dreamed of! He would commission articles from contributers via snail mail. Later when dial-up modems began to make their presence felt, he would write the commissioning letters which then his secretary would type and send via email. Publishing is a business that builds upon the creative energies and enthusiasm of many individuals but requires at the same time meticulous multi-tasking to ensure that all the scheduled tasks are being completed on time. Gordon Graham was a fine example of an exemplary publisher, a gentleman publisher, whose knowledge and experience of the industry would sit lightly. He was ever so gracious about meeting new entrants to publishing and always willing to lend an ear to their opinions. He was passionate about the industry even though he was most familiar with the academic form of publishing. He was very clued in about the different kinds of publishing in various parts of the world. All of this was remarkable given that he had accrued this knowledge on the basis of his travels, his conversations, his experience and his vast and diverse reading. A few minutes of conversation with Gordon Graham was pure delight. With this insight in the industry he had the vision to create this extraordinary journal. By the time of his retirement he was already an established publishing legend but to create a journal from scratch required hard work and determination. He made it happen. Today Logos is a journal on the publishing industry which is a fantastic repository of information, case studies, views and opinions. It is the gold standard among journals in terms of the rigour and peer review that goes into maintaining the standard of contributions. During his lifetime, Gordon Graham handed the journal over to Brill, a publishing house that had been at the time in existence for nearly two centuries. Brill is an academic publishing firm with a formidable catalogue of journals as well. So this was a perfect match in terms of strengths and expertise. By the time Logos became a part of the Brill stable, the furious debate about print vs digital had begun in publishing. Gordon Graham vision ensured the journal’s survival in the very capable hands of the editor Angus Phillips and support of Brill.

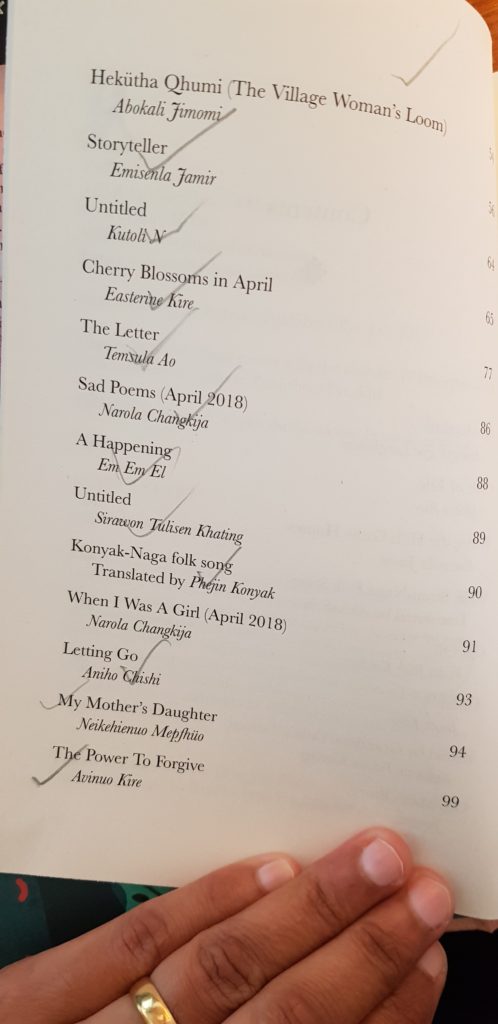

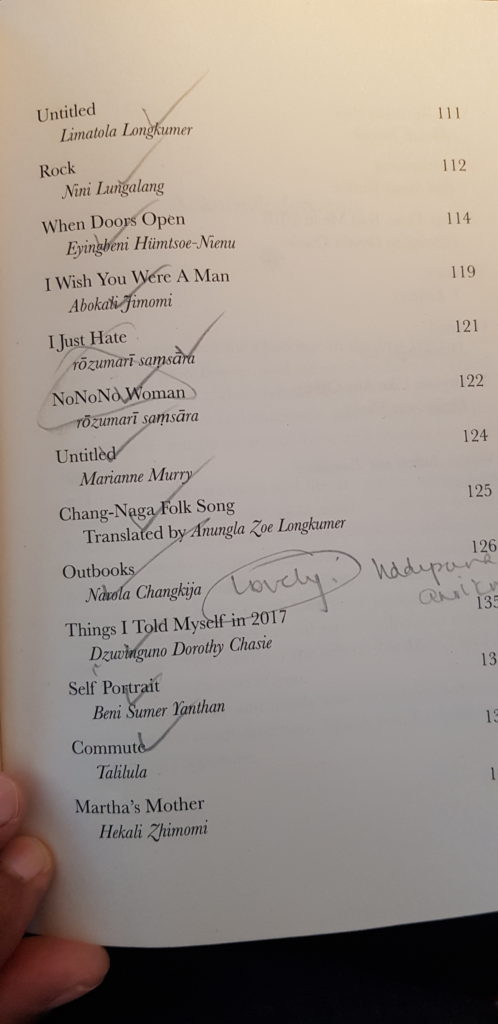

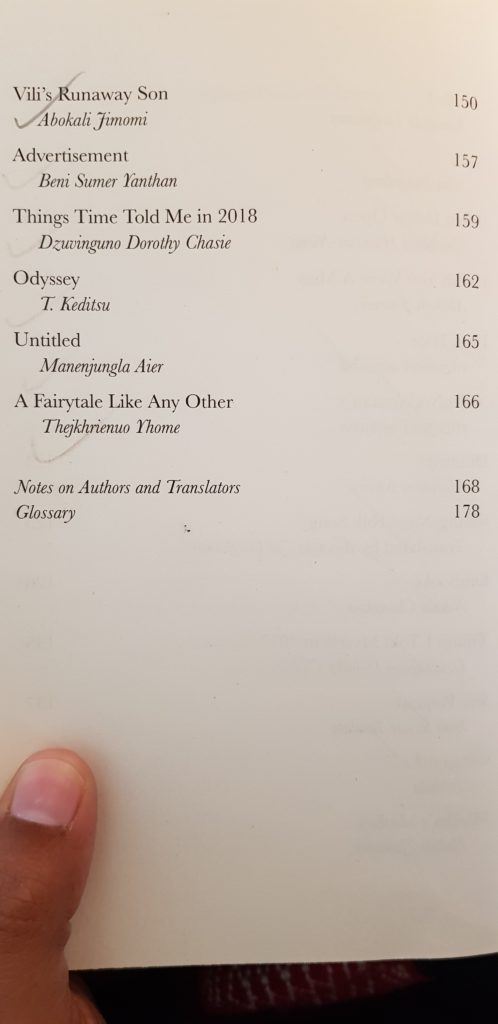

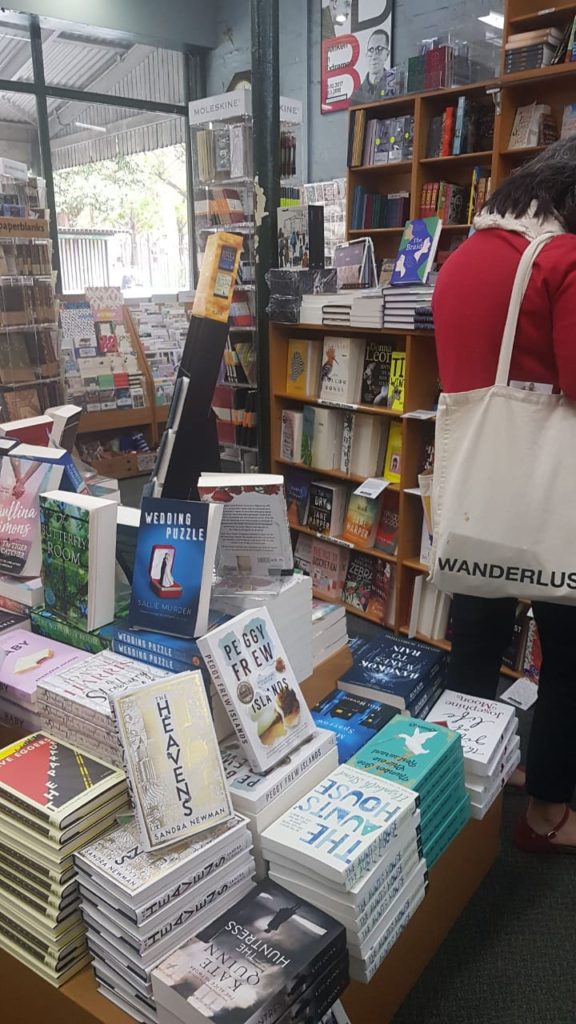

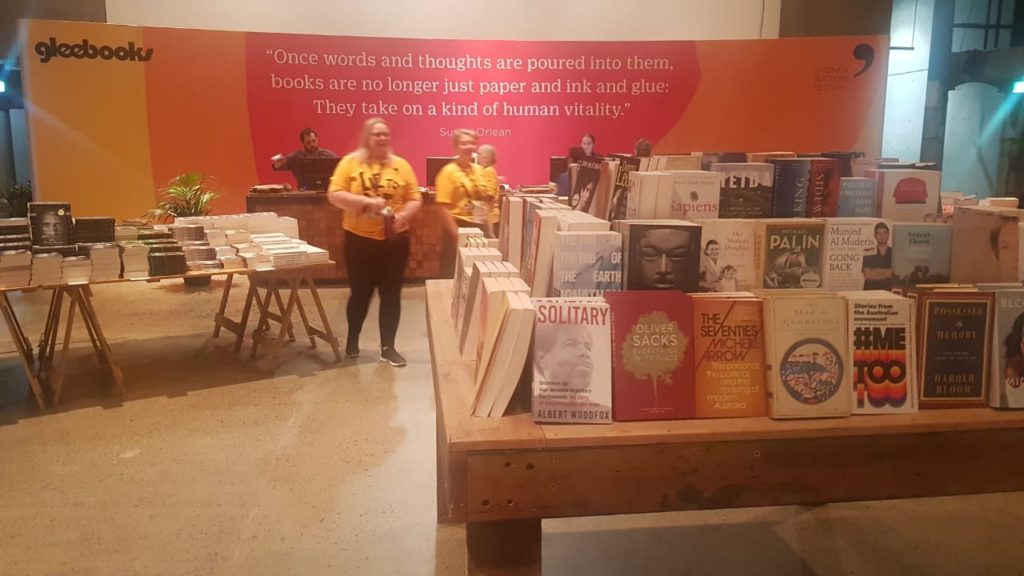

To celebrate the twenty-fifth year anniversary, a special edition, a book of selected essays on publishing were put together. It is a collection of essays worth its weight in gold. Publishing histories of successful firms or rise of authors at the best of time are tricky to document as these are mostly not documented in the moment of time. So to cobble together histories of iconic firms such as the Paul Hamlyn, Thames & Hudson, or Weidenfeld & Nicholson is a remarkable achievement which these essayists have achieved. There is a fine balance of the personal with the professional. While the histories are engrossing; it is also the realisation that certain principles of publishing do not change — it is technology which does. But through the ages everyone is preoccupied with the marketplace and assessing what readers desire. This is a concern that is of paramount importance. And this is exactly why The Cottage by the Highway is fascinating since none of the essays selected veer too far away from the central idea that publishing is a business. It is not always said explicitly but it understood. At the same time there is no denying the buzz one gets being a part of this industry. It is fun. It is exciting. It is challenging. It is creative. It is dependant upon one’s interpersonal skills. It is an ecosystem consisting of publishers, editors, writers, booksellers, distributors, agents, translators, book designers etc. Ultimately it is the coming together of experience, skills combined with business acumen to recognise where the gaps lie in the market and be prepared to put in the hard work required. For every book is akin to a designed product. It requires patience, vision and hard work for every book published.

The Cottage by the Highway is a treasure trove of publishing wisdom. It is applicable across geographies and book markets. It is much in keeping with the vision of Gordon Graham — of cross-pollination of information and experiences while attempting to document critical stages of publishing. A tiny detail that most publishing professionals forget or are too busy to do for themselves or their institutions. Read The Cottage by the Highway. And if you are a publishing professional or aspiring to be one, learn from it. It is absolutely fantastic!

18 February 2020