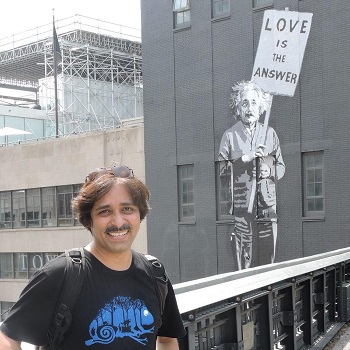

Q&A with Pramod Kapoor, Roli Books

Pramod Kapoor, the founder and publisher of Roli Books (established in 1978). A sepia aficionado, he has over the course of his illustrious career conceived and produced award-winning books that have proven to be game changers in the world of publishing. Be it the hit ‘Then and Now’ series and the seminal Made for Maharajas, or even the internationally acclaimed Gandhi: An Illustrated Biography and New Delhi: The Making of a Capital. In 2016, he was conferred with the prestigious Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honour), the highest civil and military award in France, for his contribution towards producing books that have changed the landscape of Indian publishing. He is currently working on his forthcoming book on The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny in 1946

Q 1. Roli Books is known worldwide as the publisher of fine illustrated coffee-table books. Forty years ago this was a relatively unknown space of publishing. Why and how did you venture in to this niche area of publishing?

I followed my own marketing instincts. In 1978 when I started my own venture I saw that besides Taraporevala there was no illustrated book publisher in India. They too printed the books in B/W only. Most of the illustrated books those days were imported from UK / USA and they sold well. Roli Books was result of a strategic collaboration with one of the largest printers FEP International Singapore. Perhaps the reason for the instant success was that I skilfully combined superior Indian scholarship, photography and design with world class printing and production from Singapore. Result was that distributors would pre-purchase the entire print run sometimes just on the basis.

Q2. How do you decide which topics to commission and which you will work upon yourself? What is it exactly about delving into the past that propels this excitement in you to make/commission these books for a modern audience? How do you hope to bridge the gap?

As I said earlier it was the marketing instinct and courage to take risks. We continue to publish on the same principle but now the instincts have matured with over forty years of experience in ever changing publishing world. I pick up books to work on personally largely on my personal interest. I like exploring and researching vintage visual material. That comes because of my interest in medieval and modern history. Over a period of time I have developed a keen eye for photographs and I use that skill to create books personally. Friends in publishing throughout the world help me keep abreast of the changes and I suppose because of my deep interest in visual arts I keep thinking of the newer formats to present a certain kind of work. In my mind I am engaged with my readers continuously.

Q3. How do you find the time to be a researcher/writer while managing a publishing business?

My hobby is my business. It comes naturally and when I am actively engaged in a project I plead guilty to being overly obsessive.

Q4. A lot of thought and care goes into crafting the Roli Books list — creating the text, selection of pictures/ photographs accompanying, design etc. What is the average time a project of this magnitude takes in being executed? What is the process of fact checking instituted at Roli Books?

Fortunately, my colleagues who have been with me for decades and my next generation have not just imbibed that skill but have done better. I learn from each one of them. They are at times more concerned about quality and excellence. A project can take six months to three years on an average. My personal projects on an average get published after five or six years of comprehensive research. Our kind of publishing is result of pure teamwork. A typical book goes through various filters, from authors to editors, art director to graphic designers etc. There are systems in place that fact checks at every level.

Q5. Some of the material you use in your books requires delving into archives, personal collections and literary/estates. It must be quite challenging at times to find the rightful owner of the material. Given that the 21C is considered to be an information-rich age, where content is at par with oil in value, what are some of the challenges you face while trying to get permissions in place?

Over a period of time we have established relationships and goodwill in the world of archives. That certainly helps. Though I still like and enjoy visiting archives. Technology has made it simpler. More defined copyright laws and easy enforcement also helps. Unlike before there are very few grey areas. That certainly helps.

Q6. Calcutta Then, Kolkata Now epitomises the nature of publishing Roli Books is synonymous with — making visible the old for new audiences. How was this project conceptualised and executed? Also, why did you choose to make it a “flip” book?

This is fifth book in Then and Now series. The format was first conceived with India Then and Now almost fifteen years ago after consultations with some of our international co publishers. It was not easy to convince them. Nor was it easy to sell it to our own sales team and leading booksellers. But we persisted. Each title in the series has been reprinted several times. India book published fifteen years ago is still popular and gets reprinted every second year.

Q7. Many of the books you publish are on extremely well-known topics with examples of iconic literature on the same subject. For instance, with Calcutta Then, Kolkata Now it is impossible to not recall Raghubir Singh’s classic art book Calcutta and yet both books have distinctive identities. So how do you find that particular peg to position your publication?

Sometimes it is challenge that propels excellence. Strong urge to make a better book and differently than the ones available helps to create a successful book. Raghubir Singh’s book was pure art, his personal brilliance that showed through his images of Calcutta. My book is on Calcutta as a city first and in that process I endeavoured to collect best that was in the family, personal and public collection throughout the world.

Q8. Roli Books make history accessible to the lay person — whether it was visiting the British Archives to use the appropriate image by Margaret Bourke-White in the Lotus imprint edition of Khushwant Singh’s Train to Pakistan, to Gandhi and more recently Calcutta Then, Kolkata Now. There is a strong underpinning of a historical narrative with equal emphasis on the visual element. When embarking on these projects, what comes first in production — the text or the pictures or does it fall in place simultaneously or is it more like a dance, step by step?

There is no fixed formula. In case of Khushwant Singh’s Train to Pakistan and Manohar Magaokar Men Who Killed Gandhi the text was available and from my past research I knew where the visuals were. (They are not in British Library but Time Life collection at Getty Images.) We skilfully combined them. For many other ideas like Calcutta Then Kolkata Now I strived to get the rarest of rare imagery and visited scores of old Calcutta families to look through their personal family albums hidden in their attics for decades. Of course there were other images from top archives throughout the world.

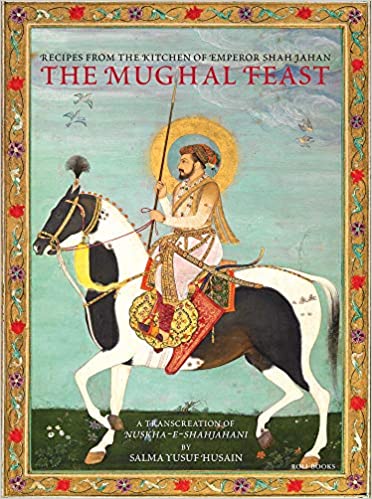

Q9. Food history is a specialised genre and fast gaining popularity among lay readers. It is timely the publication of The Mughal Feast, atranslation of Nuskha-e-Shahjahani, recipes from the time of Mughal Emperor, Shah Jahan (1628 – 58). But why is the subtitle of the book “transcreation”?

I was shown the original Persian manuscript by a friendly curator in the British Library London. We got it scanned . A facsimile copy was with us for three or four years. Salma Hussain, brilliantly translated it from Persian and added her great scholarship in adapting the recipes for modern kitchen and added a wonderful introduction. I suppose you will agree that all this amounts to ‘transcreation’.

Q10. How have the changes in digital and printing technology impacted the commissioning and production of your exquisite art books?

No they have only added to the process.

Q11. Why did a successful publishing house like Roli Books choose to expand into bookselling by establishing the CMYK bookstores?

To provide more shelf space for our titles and for world’s top illustrated book publishers like Thames & Hudson, Phaidon, TASCHEN, Abrams, etc. whom we distribute in Indian sub-continent.

Q12. What is next on the cards for Roli Books and yourself?

I enjoy picture research and that keeps me going. There are several projects which are going on simultaneously in my mind and in action. They are in nascent stage. This year I hope to finish and publish Royal Indian Navy Uprising in 1946, a non-pictorial, all text book. As regards Roli Books youngsters like Priya and Kapil can articulate that better. But I know a division creating books on Family Histories fascinates me immensely. We have recently launched a new imprint Roots for this.

22 June 2020