Over a decade ago I did a regular column for Business World. It was on the business of publishing. Here is the original url.

***

The question most often asked these days in the literary world and beyond is, “Are you going to Jaipur?” I know of authors, publishers, agents, aspiring writers and even friends who have nothing whatsoever to do with literature (not even to read a book) heading off to the Pink City. The attraction ranges from seeing authors “in the flesh” to gawking at talk-show celebrities such as Oprah Winfrey. That said, I wonder how many would actually know what a phenomenal impact Oprah’s Book Club had on book sales in America — termed as the Oprah effect. She single-handedly recommended books that she enjoyed reading on The Oprah Winfrey Show. It is estimated that the 69 books she recommended over a 15-year period, saw the sale of 55 million units. But as with popular literary spaces, she too has had her fair share of controversies. Most notably being of her recommending James Frey’s memoir, A Million Little Pieces, only for it to be revealed that the book was a complete hoax, but that is another story.

Literary festivals are spaces to have a great time — good conversation, plenty of ideas swirling about, good company, especially if accompanied by good weather, food and facilities. What more can one ask of a long weekend break? It is a mela time to listen to panelists, to be able to ask questions directly of one’s favourite authors and discover new ones. It is also a space that provides opportunities for aspiring writers to contact publishers, word-doctors, and literary agents. Rohini Chowdhury, author and freelance editor says, “I think literary festivals serve an important function in providing writers and publishers a platform on which they can come together, particularly writers who often need the visibility. It also provides them with a sense of community and turn into exclusive clubs.” William Dalrymple, director, Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF), says when he gets invited to international literary festivals as an author, he is always on the lookout for new voices or to connect with established names. It is easier to do it over breakfast than send off an impersonal email request.

A Costly Affair

But there is no such thing as a free lunch. It is never clear from the media stories that bear the cost of putting up this extravaganza. Often the stories are about celebrities attending a festival, the political and literary controversies surrounding some participants (it helps to pull in the crowds!), but rarely about the investments involved. At most there will be references to “breaking even”, but hardly any numbers are mentioned. Yet, there is a cost, and a substantial one at that to the organisers of the festival: financial and human resources and infrastructure. There is also a cost to the city that hosts the festival; although, both parties stand to gain in the long run.

Internationally, festivals are ticketed and are not the norm in India. (This is set to change with JLF announcing modestly-priced tickets for the musical events this year.) The income from ticket sales is rarely enough to cover costs of producing a festival — in fact, it is not even close, probably only 15 per cent of the total budget. So donations and sponsorship end up paying most of the costs. In addition to these, corporate sponsorship and individual donations are incredibly important to enable the literature festivals to run. A great deal of time is spent developing proposals, targeting potential sponsors (including big businessmen, bankers and financiers), sending out those proposals and following up. A festival director can send out 50 or more proposals and get only 5 or 10 responses most of which are polite rejections. Most people who generally do respond are those that already know the core team, especially the festival director’s work, so one needs to spend a great deal of time making and developing contacts. Add to this are other “hidden” costs that involve huge amounts of labour and are not easily quantified. They include planning and organising the events, particularly bearing in mind the ratio of local to international authors, as well as the linguistic ratios; keeping abreast of backlists and forthcoming titles; networking with publishers and authors; and putting together a judicious mix of ideas and entertainment. Also important are building confidence amongst participants and audience, timing the participation of authors if they are going to be in town (it helps to have information in advance as it differs the costs of running the festival). Additional costs to be factored are an honorarium or an appearance fee to be paid, especially to the star performers; organising cultural events where the artistes are paid their fee; media and publicity; salaries of the staff (permanent and volunteers); rent of the space; catering at the venue; transport and accommodation; and infrastructure. In fact, every person who walks in has a cost — registration tags (electronic or bar-coded), brochures, chair, and a system to buy a book. According to Adriene Loftus Parkins, Founder/Director of the Asia House Festival of Asian Literature, “I think it’s fair to say that no one realistically goes into this business to make a lot of money. It is very important that we raise enough to cover costs, so that we can pay our suppliers and keep going, but we are running a festival for reasons other than profit. I rarely have the funds to produce the kind of festival I’d ideally like to and to do the marketing and PR that I feel I need, so I do the best I can with what I have.”

Fundraising is a crucial aspect of organising a literary festival. An efficient team will stick to the budget and realise it is organic. Part of the fundraising is in kind – offering accommodation, free air tickets, conveyance, sponsoring a meal or an event. If it is in cash, then it is by networking with businesses, financiers, cultural and arts agencies like the British Council, Literature Across Frontiers, multi-national corporations etc. But it is crucial to find the relevant links between the festival being organised and the agency’s mandate. For instance, the British Council literature team promotes UK’s writers, poets and publishers to communities and audiences around the world, developing innovative, high-quality events and collaborations that link writers, publishers and cultural institutions. Recent projects include the Erbil Literature Festival, the first international literature festival ever to be held in Iraq; the Karachi Literature Festival; and a global partnership with Hay Festivals that has seen UK writers travel to festivals in Beirut, Cartagena, Dhaka, Kerala Nairobi, Segovia and Zacatecas amongst others. This ongoing work with partners helps provide the opportunity for an international audience to experience the excitement of the live literature scene in the UK. And for businesses it is a direct investment into the community. According to image guru Dilip Cherian of Perfect Relations, “Corporates find that they can reach otherwise with Lit Fests. It’s also an audience that captures influentials who otherwise have little space for corporate Branding. The danger though is that literary festivals may be going the way of Polo…Money too easily caught, could stifle the plot.”

The Host City Makes Hay

The business model of a literary festival depends upon who is it for — the city or the festival. According to The Edinburgh Impact Study released in May 2011, the Edinburgh “Festivals generated over a quarter of a billion pounds worth of additional tourism revenue for Scotland (£261 million) in 2010. The economic impact figure for Edinburgh is £245 million. Plus the festivals play a starring role in the profile of the city and its tourism economy, with 93 per cent of visitors stating that the festivals are part of what makes Edinburgh special as a city, 82 per cent agreeing that the festivals make them more likely to revisit Edinburgh in the future. The study calculates that Edinburgh’s festivals generate £261 million for the national economy and £245 million for the Edinburgh economy. To put this in to context, the most recent independent economic impact figure for Golf Tourism to Scotland is £191million. The festivals also sustain 5,242 full-time equivalent jobs. Although the festivals enjoy over 4 million attendances every year, the lion’s share of additional, non-ticket visitor expenditure is attributable to beneficiary businesses, such as hotels and retailers. 37 per cent (or £41 million) goes to accommodation providers, 34 per cent to food and drink establishments, 6 per cent to retailers and 9 per cent is spent on transport.”

Says Peter Florence, director, Hay-on-Wye Festivals: “We have done a hundred and fifty festivals over 25 years around the world. Just when you think you know how to do them, a new googly comes at you. The fun of it is working out how to play every delivery… .” He adds that since story telling is the basis for festival, they are open to exploring good writing in any form. Songwriters, comedians, philosophers, screenwriters and even journalists are treated with the same respect as are poets and novelists. It is all about great use of language. He clarifies that “We aren’t in business. We are a not a for-profit educational trust. We are the only part of the publishing-reading chain that is not out to make money. We simply aim to break-even and keep costs as low as possible.” Festivals grow only if the participants have a good time there. There has to be a word-of-mouth publicity for the festivals to get popular.

Frankly, it is very difficult to say that there is one clear business model for a literary festival. It changes from region to region. Yet it is obviously growing, otherwise why else would Harvard Business School be doing a case study on the Jaipur Literature Festival that is being studied over two semesters.

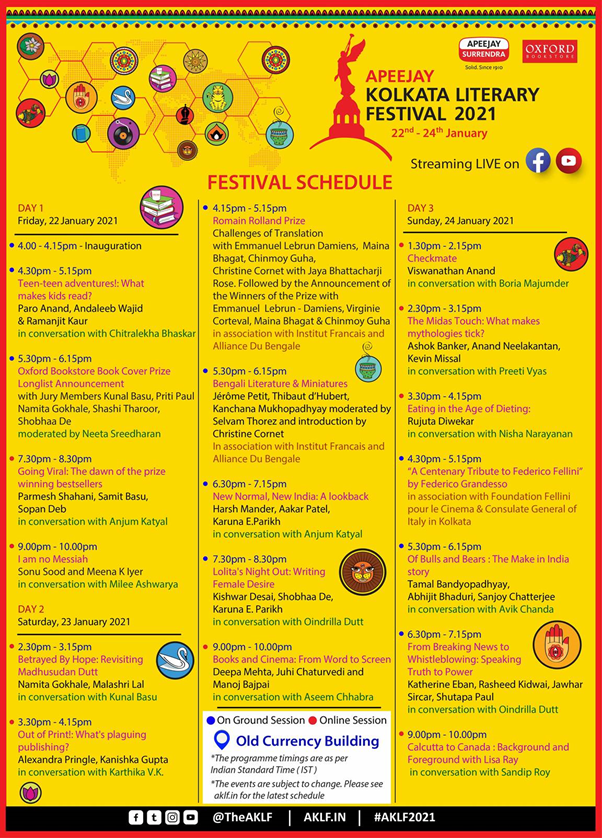

15 Jan 2021