World Translation Day

30 September is celebrated worldwide as International Translation Day. On 24 May 2017, the UN General Assembly adopted resolution 71/288 on the role of language professionals in connecting nations and fostering peace, understanding and development, and declared 30 September as International Translation Day.

30 September celebrates the feast of St. Jerome, the Bible translator, who is considered the patron saint of translators.

St. Jerome was a priest from North-eastern Italy, who is known mostly for his endeavor of translating most of the Bible into Latin from the Greek manuscripts of the New Testament. He also translated parts of the Hebrew Gospel into Greek. He was of Illyrian ancestry and his native tongue was the Illyrian dialect. He learned Latin in school and was fluent in Greek and Hebrew, which he picked up from his studies and travels. Jerome died near Bethlehem on 30 September 420.

It is interesting to note that on the Internet, 30 September is celebrated with great gusto. Translators, publishers, writers, readers, booksellers etc promote translations enthusiastically. It becomes a fantastic excuse for world literature to be made visible. Many threads pop up on social media that are worth preserving and referencing for the future. Take for instance, Meru Gokhale, Publisher, Penguin Random House India’s tweets on 30 Sept 2020.

In all this exuberance of sharing and posting images of translated works in a predominantly secular world, the key connection with the Bible is usually forgotten. Ironical that the secular calendar requires a festival to be celebrated and borrows a date from the Christian calendar. Nevertheless it is worth reading about the various translations of the Bible that were made available particularly after Gutenberg’s printing press made it technologically “easier” to provide multiple copies of the text rather than await a handwritten copy.

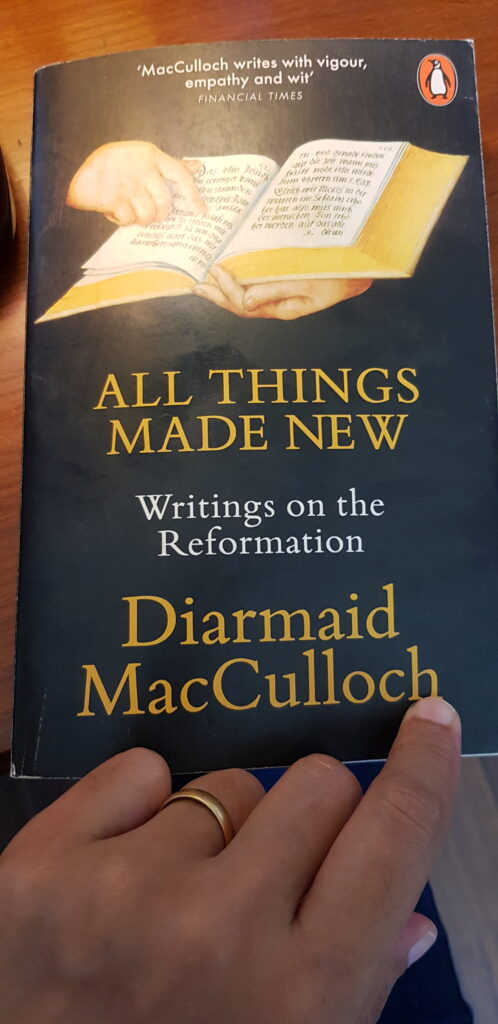

In All Things Made New: Writings on the Reformation by Diarmaid MacCulloch, Professor of History of the Church at Oxford University, there are a couple of chapters on the translations of the Bible. A neat division is made between the various translations of the Bible available before and after the authorised King James Version (1611).

Here are some relevant extracts from the chapter “The Bible before King James” ( pp. 167 – 174) that give a sense of how many translations of the text existed in circulation.

In the fifteenth centry the official Church in England scored a notable success in destroying the uniquely English dissenting movement known as Lollardy. One of the results of this was that the Church banished the Bible in English; access to the Lollard Bible translation was in theory confined to those who could be trusted to read it without ill consequence — a handful of approved scholars and gentry. After that, England’s lack of provisions for vernacular Bibles stood in stark contrast to their presence in the rest of Western Europe, which was quickly expanding, despite the disaproval of individual prelates, notably Pope Leo X. Between 1466 and 1522 there were twenty-two editions of the Bible in High an Low German; the Bible appeared in Italian in 1471, Dutch in 1477, Spanish in 1478, Czech around the same time and Catalan in 1491. In England, there simply remained the Vulgate, though thanks to printing that was readily available. One hundred and fifty-six complete Latin editions of the Bible had been published across Europe by 1520… .

The biblical scholarship of Desiderius Erasmus represented a dramatic break with any previous biblical tradition in England: when he translated the New Testament afresh into Latin and published it in 1516, he went back to the original Greek.

The next significant translation of the Bible was by William Tyndale, who is considered to be the creator of the first and greatest Tudor translation of the Bible. His is the ancestor of all Bibles in the English language, especially the version of 1611… By the time of Tyndale’s martyrdom in 1536, perhaps 16,000 copies of his translation had passed into England, a country of no more than two and a half million people with, at that stage, a very poorly developed market for books.

In 1535, King Henry VIII himself, never predictable in matters religious, achieved a first at the same time by commissioning the first Bible printed in the British Isles — not in English, but a Latin text, with selected edited highlights from the Vulgate Old Testament and the whole of the New Testament. … This was followed by the Coverdale Bible, the only one to be available in English. This was followed by a former associate of Tyndale called John Rogers, although his work went under the pseudonum of Thomas Matthew. After the Matthew Bible, Coverdale produced yet another version of his completed text that acquired the nickname of the Great Bible. Given that the preface was provided in 1541 by the archbishop, it is often called Cranmer’s Bible. Subsequently, other versions of the Bible were published — the Geneva Bible ( 1560 and 1576 with its first English printing it became a firm favourite with the reading public) and the Bishops’ Bible (1568). These were soon followed by the King James Bible ( 1611).

Diarmaid MacCulloch speculates that perhaps the 1611 vesion had such a lasting effect because of the quality of its translation.

There were so many translators on King James’s committees that the effect was not cacophony but uniformity: one translator read out his effort at revision of his allotted secion to his fellows, and they all joined in criticism and helpful suggesion to smooth out idiosyncrasies … . ( p.179)

An interesting observation on the art of translation by a scholar of a text that has withstood the test of time!

4 October 2020

No Comments